The samurai were the elite warriors of Medieval Japan. They were a social class onto themselves, serving private masters, rather than the state. They lived by a strict moral code, called bushidō, that dictated their lifestyle, attitudes, and beliefs. Today, tales of bushi conquests take mythical proportions but, in reality, these were ordinary men with extraordinary loyalty and discipline.

How to Become a Samurai

In early Japan (around 700 in the Current Era), one in four adult males were drafted into military service. They served the state, such as it was, and had to provide their own weapons. In those days, they mostly functioned as public servants.

Nearly 100 years later, those provincial garrisons were dissolved. From then on, the rural elite became the preferred warrior type. Those men were skilled in archery and horse riding.

These provincial warriors formed networks for protection - of themselves, their families, and their land holdings.

The imperial court began to rely on these private warriors, rather than on the garrisons it trained and paid. The emperor established military posts, to make the unofficial partnership legitimate. Warrior leaders received military orders, which they delegated to their legions of fighters.

It's a derivative of the word saburau, meaning 'to serve'.

By the time the first shogun seized power (in 1192), the warrior class was well established. The Kamakura shogunate raised the status of the samurai, entrusting them with the security of the estates. This trust, along with the shogunate's long territorial reach, fostered cooperation among the warrior groups.

So, the samurai became a social class. One might become a samurai if born into such a family, or a man might marry a samurai's daughter to become one. For a samurai family lacking male heirs, the government might approve the adoption of a male child.

Yes, but only until the 1590s. After that, the emperor banned peasants from carrying swords, making it impossible for this social class to rise into the samurai group.

Could Females Become Samurai?

Legally, no - but, technically, yes. Daughters born into samurai (and noble) families learned how to defend themselves.

They studied the martial arts, and mastered how to use weapons such as the naginata, a long, curved blade attached to a long pole. They also hid a kaiken, a type of dagger, in their kimono for self-defence (or ritual suicide, to avoid capture).

With that said, we know that female samurai were not uncommon. They had the weapons, training, and skills to become warriors, so some did. The historical record failed to list most of their exploits, but a few names tell of their deeds.

Bushidō and the Samurai Culture

Above, you learned that warrior groups collaborated. So, they must have had a set of rules to collaborate under. These rules, code, were called Bushidō. Translated, it means 'the warrior path' or, most commonly interpreted, the way of the warrior.

This code of conduct existed long before the samurai became a social class. It crystallised and became universal during the first shogunate, the Kamakura period (starting 1192).

Aspects of this code included:

- honour in battle

- fighting only against warriors with equal equipment/skills

- conducting oneself as a legend

- having no fear

- introducing oneself and one's lineage before fighting

- no trickery or subterfuge

Another type of warrior, the shinobi (ninja), was thought unethical. Their stealth and subterfuge were distasteful to the bushi, as those qualities did not fit within the samurai culture.

Bushidō was not a written code that fighters studied. Rather, it was a set of oral traditions, passed from one generation of warriors to the next. As such, the samurai took substantial license when displaying their bona fides. For instance, introducing oneself and lineage was often a bragging exercise, rather than establishing credentials.

During the Edo Period, under the Tokugawa shogunate's rule, samurai culture evolved. That was a prosperous time in Japan, with the shogunate launching many economic and political initiatives to improve society.

For the samurai, these changes signalled a shift away from aggression, and the traditional moral code. Loyalty transferred from the samurai's lord to the shogun, and intellectual refinement grew as important as physical skill.

Ronin in Samurai Ranks

Ronin were warriors without a master. Today, we might call them free agents, or mercenaries. With no diamyo to target their loyalty at, ronin lacked a fundamental ingredient of the Bushidō moral code.

Many samurai became ronin during the Sengoku Period (1467 - 1603), as the domains they defended dissolved.

Still, ronin were skilled fighters, and perhaps a bit more ruthless than their bushi counterparts. Particularly during the Edo Period, life was tough for the ronin. They engaged in brutal acts against government officials, foreigners, and scholars. They typically did not fight alongside the samurai.

Japanese Samurai Weapons and Strategies

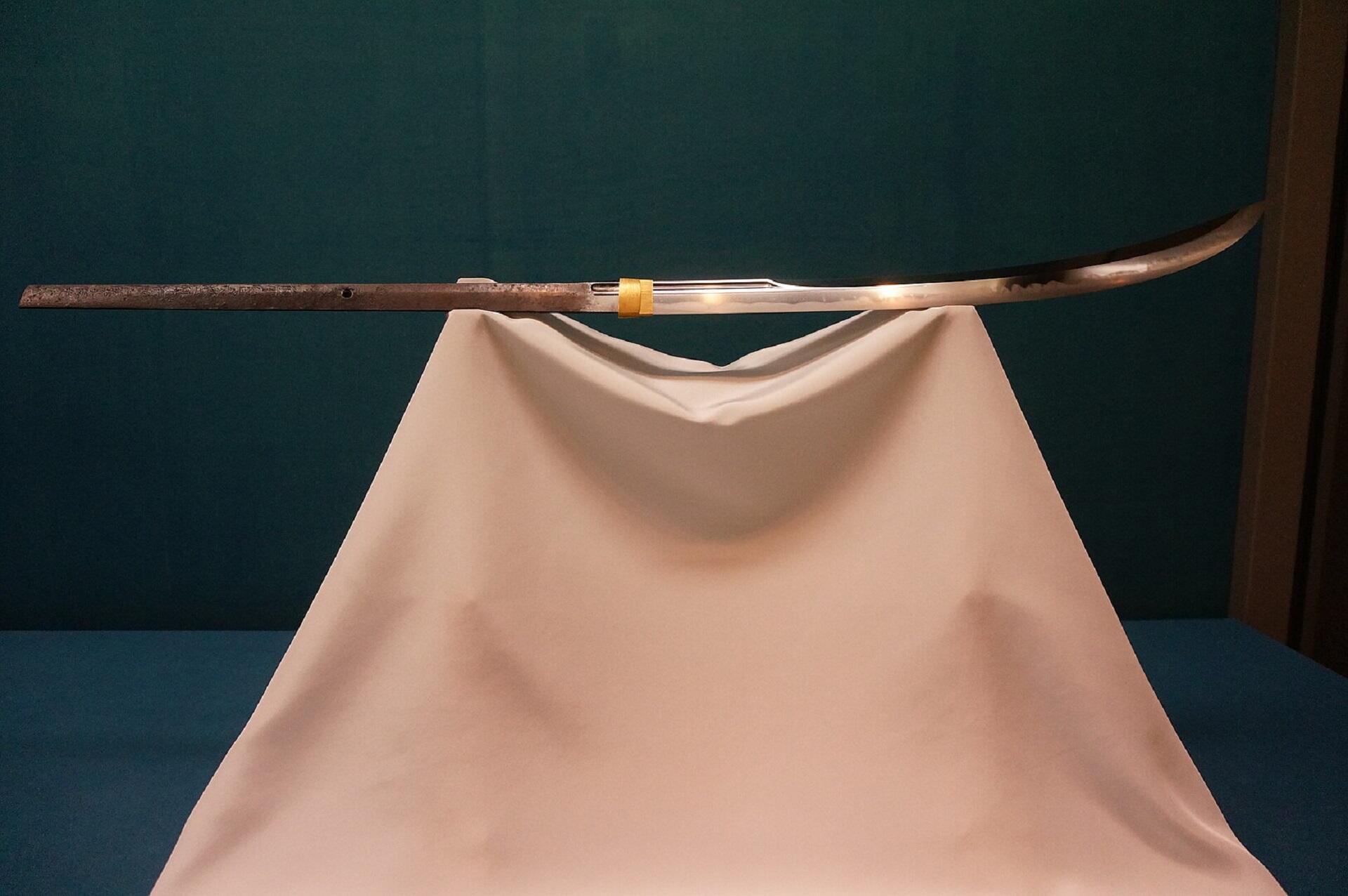

The katana, the samurai's iconic weapon, is often called a samurai sword. This single-edged, curved sword remains the symbol of the samurai's honour and status.

Though samurai culture remained much the same throughout the centuries, their weapons changed. Or, more specifically, their weapons cache expanded, as more lethal tools grew in popularity. The samurai often use a tantō, a shorter sword with a straight blade, as a backup weapon, for close-quarters fighting.

The samurai-tantō pairing, photographed above, has a name: daishō. Should a samurai lose his sword in battle, he may turn the shorter blade on himself, an act of ritual suicide called seppuku.

During Japan's shogunate period, warring was a way of life for many. The shogunate era was long, spanning nearly a millennium. So, it stands to reason that bushi arsenal changed with the times, and with fighting needs and standards.

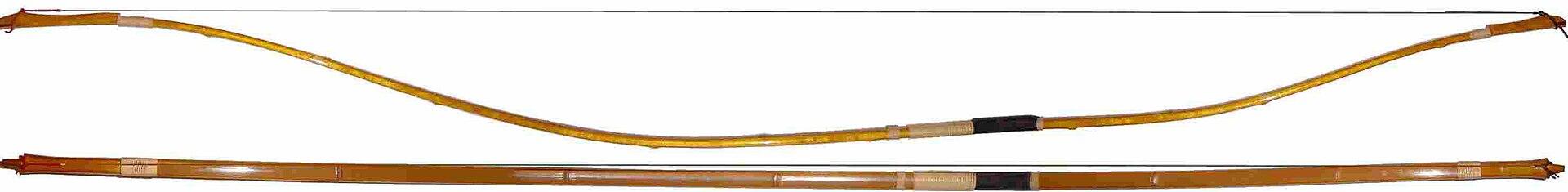

Yumi

This asymmetrical bow is more than two metres long, featuring a long upper arc, and a shorter lower bend. It is designed for samurai on horseback to fire as they ride. The proper hand placement is roughly 1/3 of the way from the bottom of the bow.

Naginata

This weapon consisted of a long, curved, single-edged blade mounted on a long pole. It features a round tsuba (hand guard) between the blade and shaft.

This weapon's unique feature is its removable blade, as the weapon is held together with a wooden pin. Though both genders used this weapon, the naginata was the favourite of the female samurai.

Yari

The yari is a type of spear. Its blade length varies, from just a few centimetres, to a metre or longer. The yari's distinguishing feature is its tang, which was longer than its blade. Yari shafts were long and typically decorated with engravings, semi-precious metal bands, or other markers.

Kabutowari

This weapon resembles a filet knife, though it's much sturdier, and has a hook near its tang. Its name translates to 'skull breaker' or 'helmet breaker'.

It has a short handle and a long blade, ending in a dirk-like point. Samurai used it to separate armour plates, hook helmet cords, or parry their opponent's sword at close range.

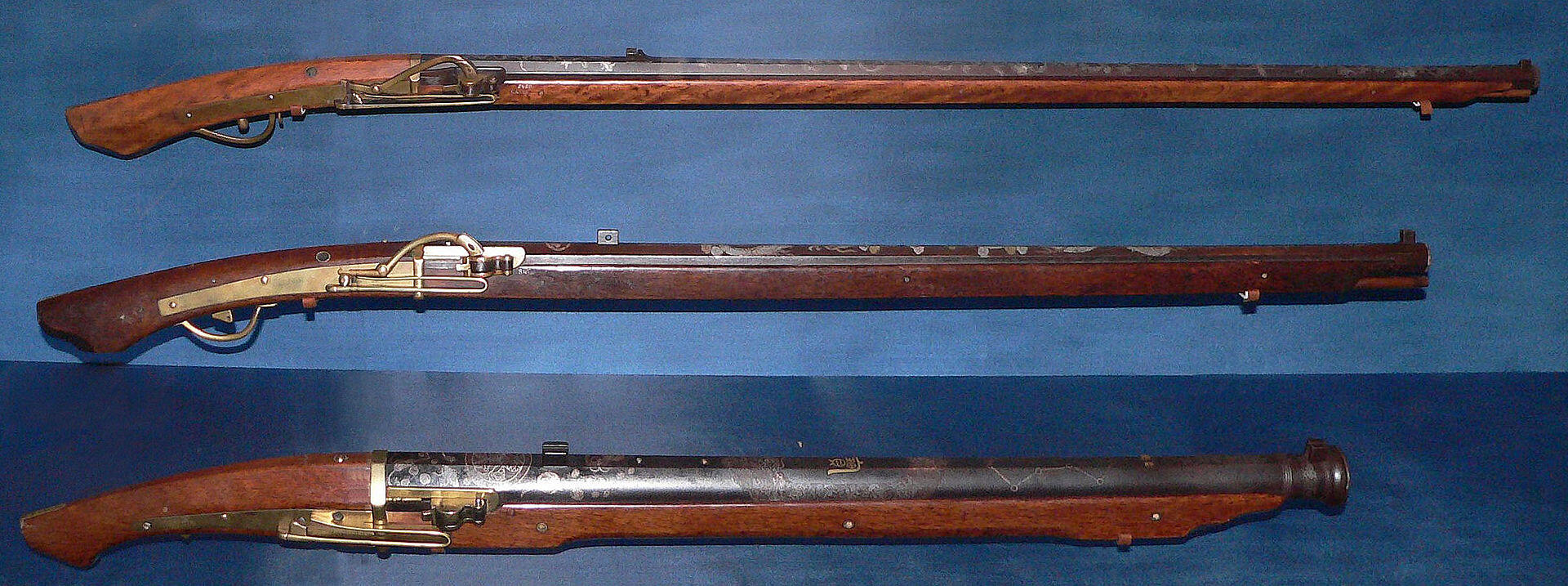

Tanegashima

This was a type of arquebus. This long firearm came to Japan, courtesy of the Portuguese, in 1593. The samurai and foot soldiers (ashigaru) used this weapon, and changed the nature of war. Still, they did not abandon their traditional weaponry; the yumi remained a part of their arsenal despite the gun's distant reach.

Why Were the Samurai Abolished?

In general, life in shogunate Japan revolved around a hierarchical structure, with these warriors taking their place just under the nobility ranks. A family living by samurai values accorded those people social status and preferential treatment. For daughters of the peasant class, being a maid to a samurai family made them sought-after marriage material.

Inevitably, this way of life had to end.

The blunt fact is that there was no longer a point or need for samurai.

The House of Tokugawa had done much to unite the country's various holdings, and brought a measure of peace to warring factions. The diamyo, appeased as they were, and secure in their status, had no need to send their warriors into battle.

So, the samurai languished. To be sure, they kept up their training, and still lived by their moral code. But their value - their contributions to Japanese society - was greatly reduced. This state lasted for roughly 250 years, the duration of the Edo Period. When the feudal era ended in Japan, in 1868, the samurai found themselves with no master to defend or fight for.

This is the way the world ends. Not with a bang, but a whimper.

T. S. Eliot, from The Hollow Men

This quote echoes the sentiment and climate as the clock wound down on the time of the samurai. The fall of shogun rule, the Meiji Restoration, and Japan's subsequent opening up, ended the need for samurai warriors.

The more fortunate of these men, whose diamyo were well-connected, took positions in government. Those less fortunate, whose lords were not a part of the new governing structures, were cast adrift.

Inactivity and the lack of compensation led these warriors to seek paid positions as teachers, artists, and bureaucrats. Thus engaged, they no longer had the time to cultivate their fighting skills. By the time the samurai class was abolished, the warriors had already anticipated their loss of culture and way of life.

Summarise with AI: