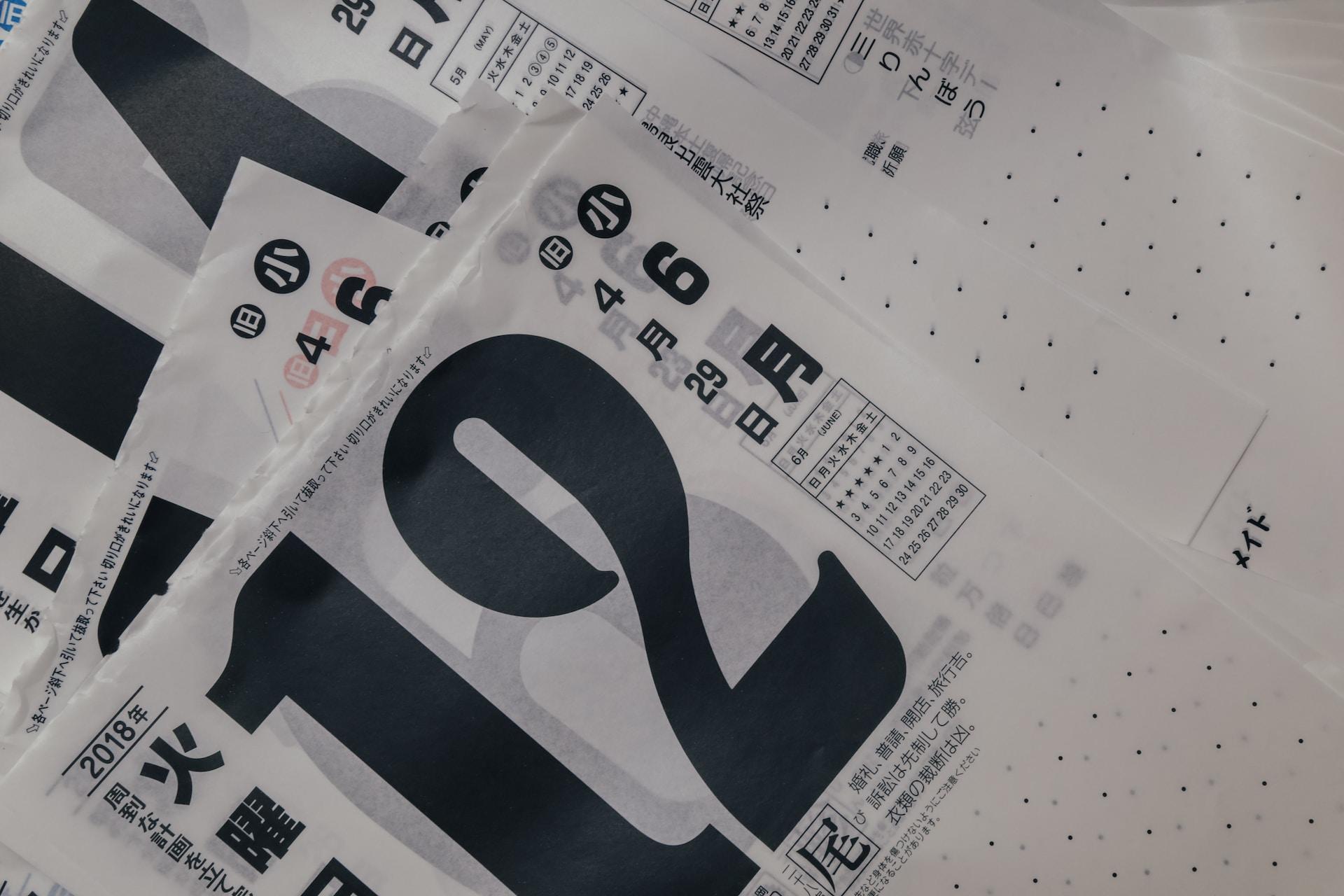

Learning the Japanese writing system seems like a complex undertaking. Even the most ardent language learning enthusiasts might find Japan's three 'alphabets' daunting. But this language's vocabulary and numbering systems are more logical than our native language's.

Once you can read Kanji (Chinese characters) and Hiragana (syllabary for Japanese words), you too will marvel at how easy it is to count in Japanese. The pronunciation of the numbers in Japanese is easy to master, too. Superprof is here to help you learn about Japanese numerals.

We'll first go over Japanese numbers and explore some key differences between how we count and how Japanese native speakers do it. We'll also give a short lesson on measure words - they're far more crucial in Japanese. And then, to end on a high note, we'll share some fun facts about numbers in Japan.

An Overview of Japanese Numbers

If you're like most people, you developed a numbers sense before you could properly talk. Except for people afflicted with dyscalculia - the numbers equivalent of dyslexia, most people have an instinctive understanding that three is more than two, eight is less than ten, and so on.

Japanese numbers fit more clearly into a sequential system of counters than in English. Neither the English 'one' nor its numerical representation (1) gives any hint of its value relative to two or 10. Contrast that with numbers written in Kanji: 一,二,三 and so on. These number representations make it clear that one is less than three.

Kanji are Chinese characters the Japanese language uses to write names and numbers. Proper nouns, verbs, adjectives - anything that communicates an idiomatic meaning has a Kanji character - as Japanese names typically do. Written in kanji, the numbers look like:

| English | Kanji | Phonetics | Hiragana |

| zero | 零 | rei | れい |

| one | 一 | ichi | いち |

| two | 二 | ni | に |

| three | 三 | san | さん |

| four | 四 | yon, shi | し ; よん |

| five | 五 | go | ご |

| six | 六 | roku | ろく |

| seven | 七 | shichi or nana | しち ; なな |

| eight | 八 | hachi | はち |

| nine | 九 | kyū or ku | きゅう;く |

| ten | 十 | jū | じゅう |

You'll note that numbers 4 and 7 have alternate pronunciations. That's due to the superstition around the 'shi' particle. A single 'shi' could mean 'death'; the doubled sound could be a homophone for 'place of death'. As for ku (9), that's one way to say 'agony'.

Today, these superstitions are less prevalent. Still, these alternate pronunciations have found their own meanings. Most native Japanese speakers avoid shichi when talking about seven-year-olds, for instance. But shichi is suitable to tell someone the time.

From here out, Japanese counting is nothing but logical. Instead of changing whole words - like our eleven, twelve and thirteen, you only need to add jū (十) in front of each number. Thus, we end up with 十一,十二,十三 and so on, up to 十九. To write 20, simply write 2 10 - 二十. The pattern continues through to 90 (九十).

From 21 to 99, Japanese numbers feature three characters, save for the 'tens' - 20, 30, 40 and so on. Beyond them, these numbers are made by saying or writing how many of that ten there are: 三十七 represents 37 (san jū nana - three ten seven).

In Japanese, 100 is written with 百 (pronounced hyaku). Counting beyond this, as you may have guessed, follows the same logic as the ten numbers. For instance, 237 is 二百三十七 (ni hyaku san jū nana) . If you only need to write 137 in your counting, you don't have to add any numerals in front of 百.

Key Differences Between Japanese and Western Numbers

You'll note that the Japanese numbering system seldom includes zeros even though zero has kanji and hiragana representation. In English, we use zero as a placeholder. In Japanese, the reader or listener understands the quantity described by how the numbers are ordered.

The Japanese number system is remarkably consistent, too. Even Sen and Man (one thousand and ten thousand, respectively) follow the same pattern. Thus, instead of writing a four- or five-digit number, you only need to write 千 (thousand) or 万 (ten thousand). Thus, our 20,037 is 万三十七.

The only time you might use zero is when the number has its own value or meaning. For instance, you might say "There are zero people here", although you'd probably just sayここには人がいません - there are no people here. Likewise, you might see "無料 - muryō" which means free, rather than zero yen.

By comparison, the English way of using numbers seems clunky and complicated. Not just with the tween word changes - 11, 12, and 13. But also with saying 'and' between numerals. Writing 'one hundred and one' is far more complex than 百一. Luckily, we dropped the archaic 'four and twenty' structure long ago.

Grouping numbers is much simpler in Japanese. To wit, Japan considers thousands (千 pronounced sen) as the main threshold for group classifications, maxing out in the uppermost 10,000s (万, pronounced man). For numbers greater than 万, you only need to add a multiplier in front of it. For instance, one million is 百万; half that amount is 五十万.

One hundred then thousands (and fifty ten thousands) might seem overly convoluted if you're not used to this numbering system. If this seems confusing, rest assured that regular study of Japanese words and phrases will make this system second nature.

Lucky and Unlucky Numbers

In the last segment, we touched on the Japanese numbers 4, 7 and 9 having alternative pronunciations. The Japanese kuu (9) sounds like 苦, which means pain and suffering. Play it safe and use the kyuu pronunciation whenever possible. Shi (4) sounds like 'death' (死) so it's best to avoid the 'shi' pronunciation as much as possible, particularly if you're talking about living things.

Seven is pronounced 'nana' when talking about the age of something, whereas shichi is for the time and date. Therefore, if you're thirty-seven years old, you are san jū nana, but if you‘re talking about the year 1987 for example, you'd say: sen kyū hachi shichi (千九八七).

Japanese talisman numbers are considered fortunate. The prime numbers 1, 3, 5 and 7 accord beneficial effects in Japanese culture. It's common to incorporate homonyms of ichi, san, go or nana into children's names to encourage prosperity.

The number eight, though not prime, is also a lucky number because its kanji resembles arms spread wide to welcome fortune. There is also a role that the kanji and kana play in this sequence. It's worth thinking about how the Japanese alphabet plays into investing someone with lifelong good fortune too.

Measure, Counter, and Token Words in Japanese

By now, you have an idea of how easy it is to count, write, and speak numbers in Japanese. Learning how to use numbers in context takes a bit more study. Understanding Japanese culture helps a bit but you must also know and understand Japanese grammar.

In English, we're rather negligent about using measure words. For example, we might like to go for a coffee, but in Japan, you would go for a cup of coffee (一杯; ippai - one cup). Should you describe your family to someone, you need a measure word for them, too. Rokunin (六人) indicates 6 people (人) in your household, for example.

Person (人) is among the few predictable measure words in Japanese; it refers only to people. Other measure words group objects together by shape or defining characteristic/s. Thin, blade-like objects like paper and knives use the mai (枚) measure word.

Long, round or cylindrical objects are -hon (本) because they resemble tree logs. Conversely, the measure word for books and other things made from wood is also 本.

The measure word ko (個) is for describing small things like eggs or ping-pong balls. To describe household appliances, use 'dai' (台). Key measure words for time include: -gatsu (月) for months, -nichi or -ka (日) for days and -fun or -pun (分) for minutes.

Outside of perhaps the military, English speakers hardly use measure words. "I'll have the soup" is common restaurant parlance even if you say to yourself that a bowl of soup is just what you need. And it's a safe bet that you've never said "I have one each stove in my kitchen, as well as one each refrigerator". I haven't, either.

As you learn the basics of Japanese, you needn't focus too much on measure words. To start, you can use the universal measure word tsu (つ). Japanese speakers will understand you but you won't be grammatically correct.

If you need a caffeine boost before you leave the airport, it's okay to ask for "hitotsu" coffee upon landing in Japan. But you need to learn and use the proper measure words as soon as possible.

Native Japanese speakers will appreciate your willingness to learn and your respect for their language and culture. And you'll have the satisfaction of learning how to speak Japanese correctly.

Summarise with AI: