In the 20th century, huge strides had been made to include more women in the art world. There still was, and is, more work to be done in this area, but generally, women were facing fewer obstacles than before. Thanks to better accessibility to art education, Georgia O’Keeffe was introduced to painting at a young age, and the rest is history. Find out more about this famous female modern artist and her most well-known paintings.

Early Life and Education

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe, the second of seven children in her family, was born in 1887 in a farmhouse near Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, USA. When she was a small child, Georgia showed a penchant for the arts, which her mother encouraged. She was sent to learn artistry with a local painter, and by age 9, the young girl knew she wanted to become a serious artist.

O’Keeffe attended the Art Institute of Chicago in 1905. Unfortunately, she contracted typhoid fever in 1906 and had to suspend her studies for a year. After recovering, she travelled to New York City to take classes with the Art Students League, where she learned realism under the instruction of several talented teachers.

All along the way, O’Keeffe was known for her artistic skills and her mastery of the canvas, especially in the style of realism, which was the primary art style taught to students.

Learn how to utilise different painting techniques with painting classes Brisbane.

O’Keeffe expanded her art education and influence independently by visiting art galleries.

One in particular would prove to be the most influential in her life: 291, a gallery in New York City run by photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen.

291 promoted photography and avant-garde work by modern Western artists, inspiring O’Keeffe to experiment with styles other than realism.

In 1912, she began art classes at the University of Virginia with Alon Bement, who introduced her to Arthur Wesley Dow. She was inspired by Dow’s approach to composition and design, which included using principles of Japanese art and simplifying forms to capture their essence, rather than the details. She used these new ideas to experiment and create her personal style, which became more abstract and even expressionist.

One of the first women to break into the art scene was Artemisia Gentileschi, who paved the way for all future female artists.

Relationship with Stieglitz

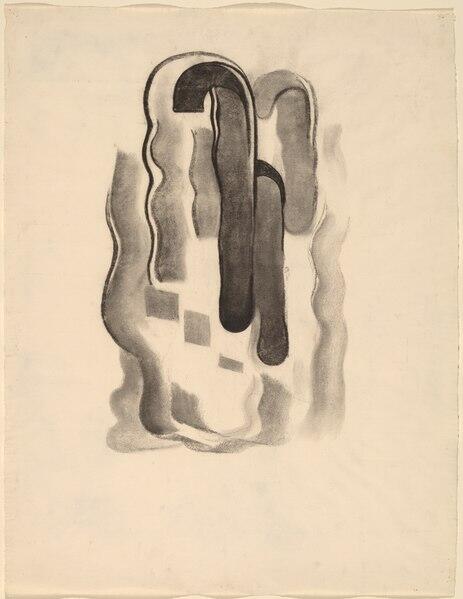

After realising she vastly preferred this new chapter of her art, O’Keeffe destroyed all her previous work; it was no longer representative of her artistic vision. Her next step was creating highly abstract charcoal drawings. She sent a few of these experiments to a friend in New York, who showed them to Mr. Stieglitz of the 291 gallery. Stieglitz was highly impressed with her work and, in 1916, included O’Keeffe’s art in his gallery. Two years later, he convinced O’Keeffe to come to New York and be an artist full-time.

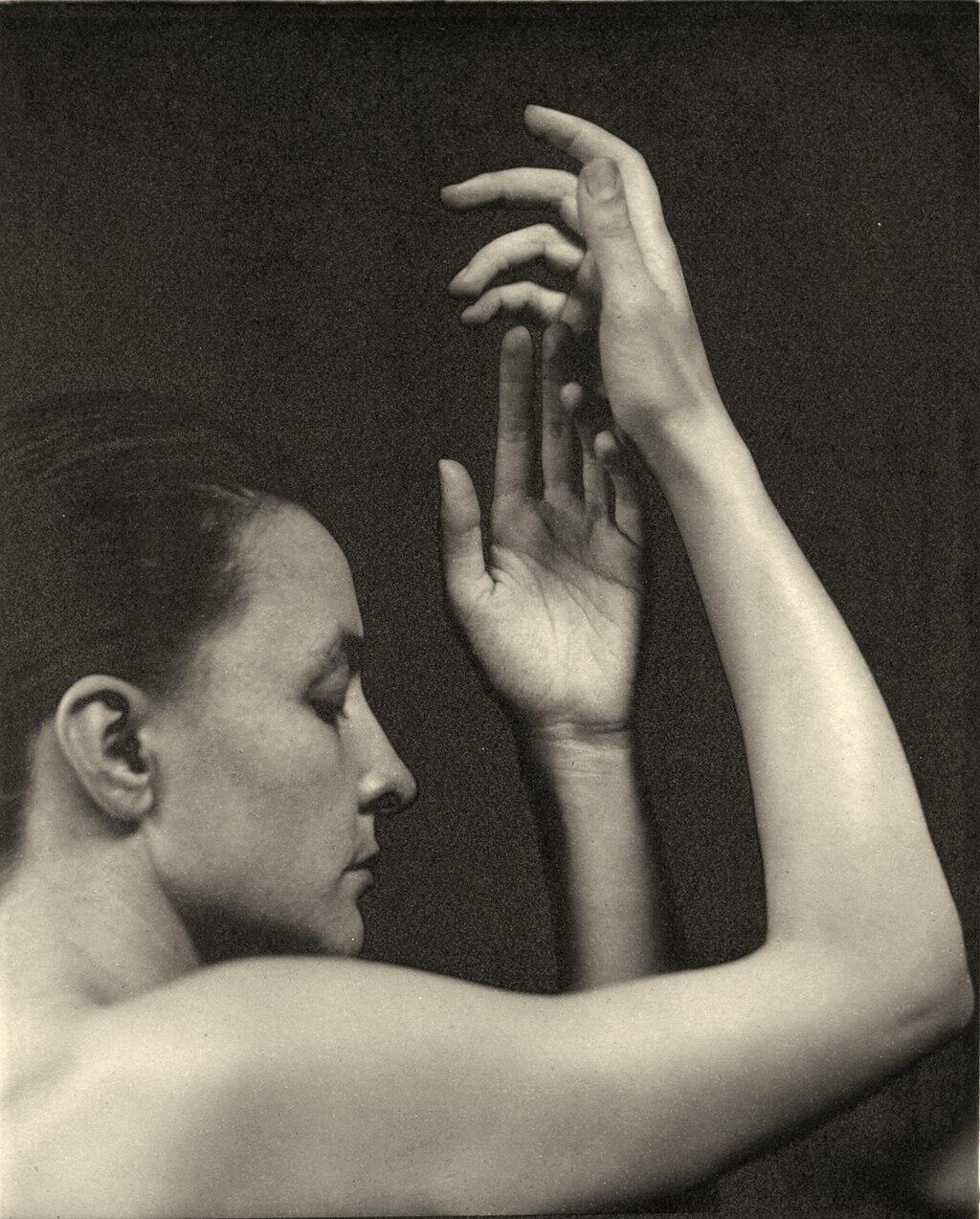

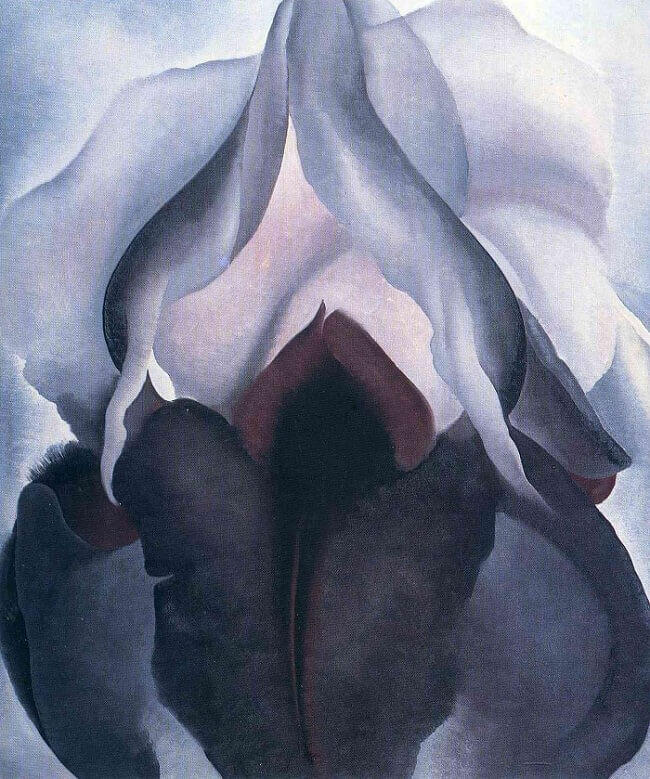

From 1918 to 1946, Stieglitz arranged 22 solo exhibitions and dozens of group exhibitions for O’Keeffe. The two were married in 1924. Over 20 years (1917-37), Stieglitz, inspired by her as a muse, photographed O’Keeffe over 300 times. Many of these photos were mundane and artistic, many with the model posing alongside her art, but some featured O’Keeffe nude, which inclined viewers to believe her botanical paintings were erotic in nature–a misconception she vehemently opposed. This was a common problem faced by women in art, such as in Mary Cassatt's case.

The two were married until Stieglitz’s death in 1946. Their entire relationship was a passionate and tumultuous one. It began while Stielgitz, much older than O’Keeffe, was still married to his first wife, when he would take nude photos of Georgia in secret. After being discovered, he moved out and lived with Georgia. In 1929, in an effort to rediscover herself, O’Keeffe travelled to New Mexico alone, a trip she would take every summer afterwards.

In this time, she and her husband exchanged a prolific amount of meaningful letters, as they had throughout their entire relationship, even before 1918. Yet, Stieglitz was deeply jealous and insecure in the relationship.

His attachment led to him having an affair with a married, much younger woman, Dorothy Norman, who was also a photographer.

The affair lasted for the rest of his life, deeply damaging his relationship with O’Keeffe (who knew about it), yet the two continued to have a deep love and fondness for one another–from a distance.

Learn various painting styles with painting classes Perth.

O’Keeffe’s Artistic Journey

In her learning years, O’Keeffe’s art was more focused on realism, often depicting still-life compositions. She worked in a variety of mediums, including watercolour, oil painting, and sketching. It wasn’t until her classes with Dow that she had her real artistic breakthrough.

In her time, and especially in the 70s, the feminist perspective was that of course a female artist would be exploring and celebrating the female body and sensuality in her paintings. However, that was not a label O’Keeffe wanted her or her art to be saddled with; she just wanted to convey the beauty already available to those who could see it. Couldn’t she just be a painter, rather than a female painter?

Experiments with Abstraction

After her classes with Dow, in 1914, O’Keeffe created a series of charcoal paintings (that she called Specials) that broke down motifs from nature into pure abstract forms. From 1916 to 1918, O’Keeffe lived in Texas, where she was inspired by the open space. Using watercolour, she continued to explore abstract designs found in nature, including the sunrise.

Learn how to create art like O'Keeffe with a painting course Melbourne here on Superprof.

Objective, Perspective, and Scale

After moving to New York, O’Keeffe began combining ideas and creating different series and styles of paintings interchangeably. She was enthralled by the concept of portraying exactly what she saw in the world; to her, the abstract forms and shapes and the details included and excluded were objectively truthful to her experience.

This era was the start of her botanical portfolio for which she is best known. About flowers, and about portraying them larger-than-life, she said:

In a way—nobody sees a flower. Really—it is so small—we haven’t time. I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.

Georgia O'Keeffe

She truly wanted to convey the hidden beauty in the details and the abstract forms of flowers; that they might evoke a viewer to see references to femininity is a coincidence.

She also created a series of paintings depicting the New York City skyline. Viewing these particular paintings, you can see how O’Keeffe slowly lost her love of the city. The paintings go from glamorous, inspired, albeit a little oppressive, depictions of the Radiator Building and the Shelton to gloomier scenes showing the concrete jungle with smog.

Discover painting classes Adelaide here on Superprof!

Even during this era, it’s evident that O’Keeffe preferred nature over the city, since she mostly painted landscapes, botanicals, and rural scenes based on the Stiegltiz family’s summer home in Lake George, New York. In 1926, she painted Black Iris.

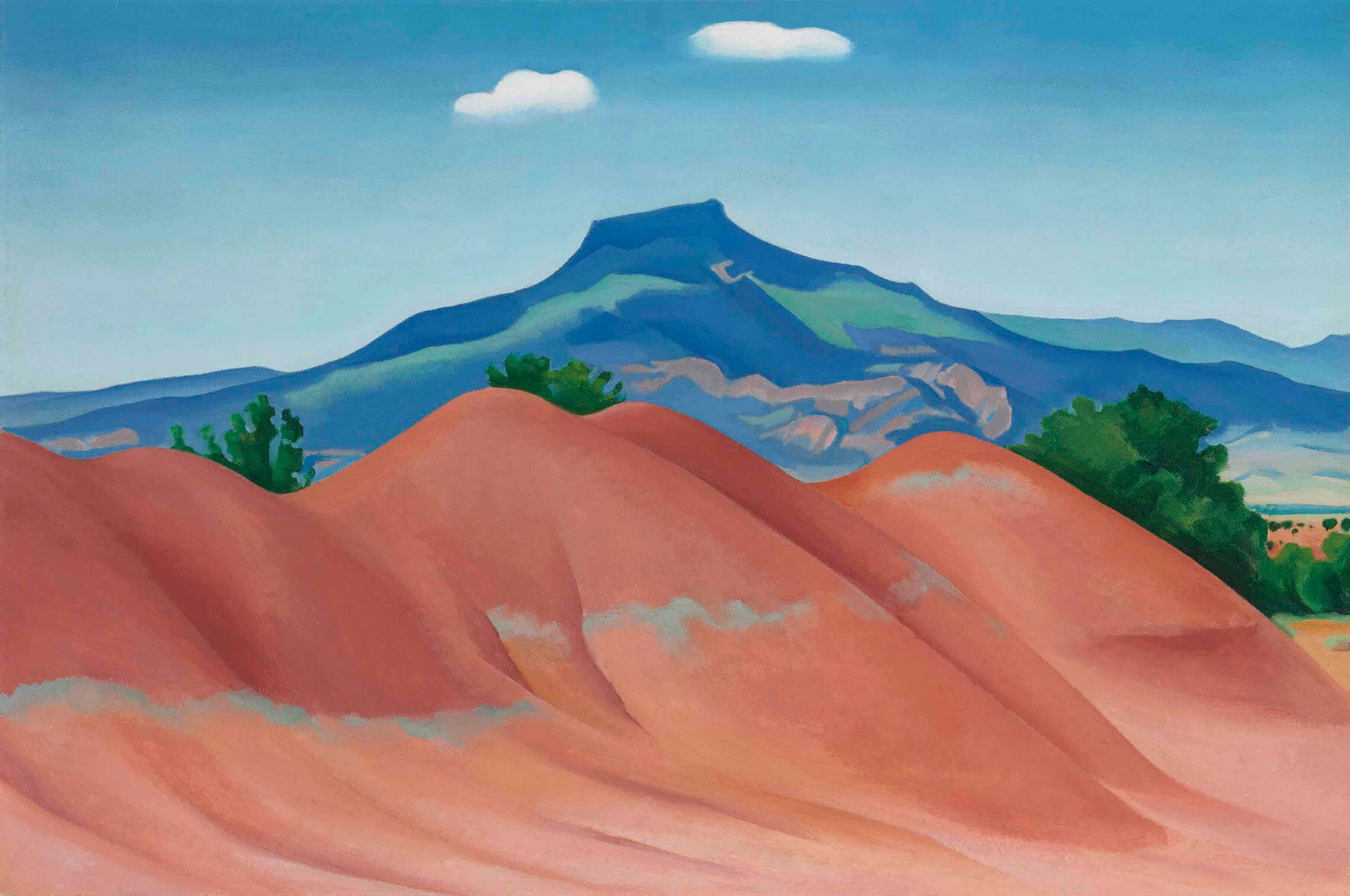

In 1929, Georgia travelled to New Mexico to reinvigorate her spirit, and she fell in love with the nature and wide open spaces there; the complete opposite of NYC.

Precisionism and the Birth of American Modernism

Around 1920, the American art movement known as Precisionism started becoming popular. It combined elements from Cubism, Dadaism, and Futurism in a uniquely American way because the subject of the art was always quintessential American things, like the landscape and cultural cornerstones.

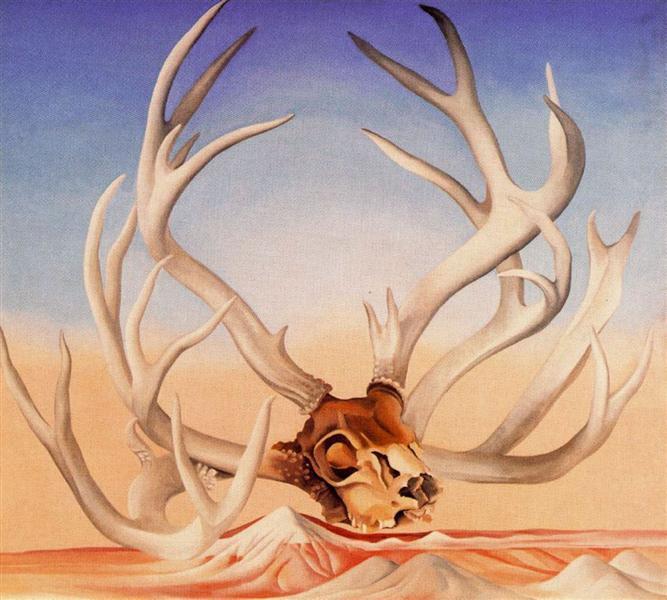

O’Keeffe’s exploration of abstraction in form and shape, and certainly her city paintings, fall into this movement. But, she then steered her interpretation of the movement back to nature in her depictions of flowers, landscapes, and eventually cow skulls.

Georgia O'Keeffe artwork popularised Precisionism, and her style morphed into and became known as American Modernism. This is why she is known as the Mother of American Modernism.

Artist Helen Frankenthaler was another pioneering woman who changed the landscape of the art world!

Faraway Era

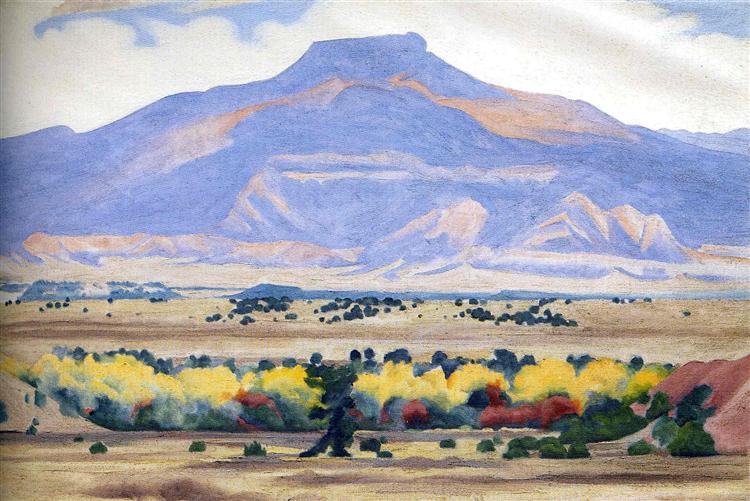

O’Keeffe called New Mexico “the faraway.” It became her refuge. The landscape, weather, architecture, and Navajo culture all inspired her to create more nature-centric art.

During these summer trips is when she would paint works such as Jimson Weed (1932) and Cow’s Skull: Red, White and Blue (1931).

Other paintings from this time include many of the most famous Georgia O'Keeffe landscapes:

- Purple Hills Ghost Ranch 2 / Purple Hills No II (1934)

- An Orchid (1941)

- My Front Yard, Summer (1941)

- Pedernal (1941-42)

- Cliffs Beyond Abiquiui, Dry Waterfall (1943)

Find painting classes near me on Superprof.

After travelling to New Mexico each summer for a few years, O’Keeffe’s art was reinvigorated. Unfortunately, her spirit was still worn down.

In 1933, O’Keeffe suffered a nervous breakdown, likely caused by her husband’s affair, combined with a commission job at Radio City that kept going wrong, plus her possible depression and anxiety. She recovered with help from a hospital and support from other women, including contemporary artist Frida Kahlo.

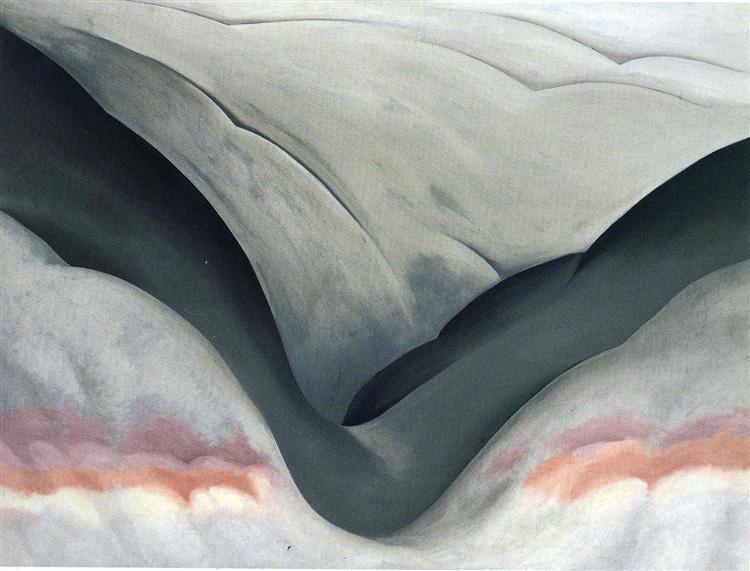

After recovering, she continued to summer in New Mexico, developing more new ways to explore abstraction, like her Pelvis series.

In 2014, O'Keeffe's Jimson Weed (1932) surpassed its estimated value of $15 million USD. At auction, it was sold for $44.4 million: the most expensive painting by a female artist ever sold.

O’Keeffe, Independent

In 1946, Stielgitz died of a heart attack. Although they had been estranged at the time, O’Keeffe attended to him in the hospital while he was unresponsive. After his passing, she moved permanently to New Mexico. Here, she continued her dedication to creating art and abstracting animal bones and landscapes onto her canvas.

Some of her most well-known works from this time include:

- Black Place, Grey and Pink (1949)

- Mesa and Road East (1952)

- Black Door with Red (1954)

She also began travelling the world. Looking out the window in the aeroplane, she was inspired to portray a new type of landscape.

Some of the works inspired by these trips harken back to her abstract charcoal drawings from decades earlier, such as Drawing X (1959), which is an abstraction of the view of a river from the sky.

Others portrayed a new type of landscape that enamoured O’Keeffe, like Sky Above Clouds, IV (1965).

Find the best painting courses Sydney here on Superprof.

By the time she was 73 years old, in 1972, Georgia’s eyesight had declined due to macular degeneration. In this year, she completed her last unassisted paintings, including Black Rock with Blue Sky and White Clouds. Her very last unassisted painting was The Beyond, a calm, yet ominous, painting.

She stopped making art for a few years, but still felt the desire to create. Her solution was to work with her full-time personal assistant, Belarmino Lopez, directing him to mix the paint, dip the brush, and direct her hand to apply it to the canvas to create the things she could still see in her mind’s eye. One such painting is Sky Above Clouds/Yellow Horizon and Clouds (1977). She also started working with clay.

She passed away in 1986 at age 98.

In celebration and recognition of the great female artist, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe (with a second branch in Abiquiu) opened 11 years after her death, in 1997.

O'Keeffe is just one of the many incredible female artists in history!

References

- About Georgia O’Keeffe. (n.d.). In The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. https://www.okeeffemuseum.org/about-georgia-okeeffe

- Ehrnst, L. (n.d.). Engl Library & Archive: Georgia O’Keeffe: Biography and Timeline. In okeeffemuseum.libguides.com. https://okeeffemuseum.libguides.com/guides/okeeffe/biography

- Georgia O’Keeffe. (n.d.). In The Vision & Art Project. https://visionandartproject.org/artists/okeeffe-georgia-bio

- Georgia O’Keeffe - Paintings, Quotes & Facts. (2024). In Biography. https://www.biography.com/artists/georgia-okeeffe

- Georgia O’Keeffe Paintings, Bio, Ideas. (n.d.). In The Art Story. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/okeeffe-georgia

- Haven’t the Heart to Destroy This One. (2018). In Musée Magazine. https://museemagazine.com/features/2018/2/7/havent-the-heart-to-destroy-this-one

- Messinger, L. M. (2004). Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. In www.metmuseum.org. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/georgia-okeeffe-1887-1986

- O’Keeffe and the Flower Equation. (2018). In North Carolina Museum of Art. https://ncartmuseum.org/okeeffe_and_the_flower_equation

- Precisionism - An empty utopia. (n.d.). In Obelisk Art History. https://www.arthistoryproject.com/timeline/modernism/precisionism

- twssmagazine. (2016). Georgia O’Keeffe: the reluctant ‘female artist.’ In That’s What She Said Magazine. https://twssmagazine.com/2016/09/14/georgia-okeeffe-the-reluctant-female-artist

- In workers.dev. workers.dev. https://www.c-span.org/program/vignette/life-and-artwork-of-georgia-okeeffe/300019