Paul Cézanne, a key figure in both Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, significantly influenced the development of Cubism. Over his nearly fifty-year career, he produced over 900 oil paintings and 400 watercolours. Despite his limited recognition during his lifetime, his art gained substantial acclaim posthumously.

Though Cézanne was not widely celebrated by audiences of his era, his contemporaries admired him deeply and drew inspiration from his work and persona. His experimentation with colour, style, and composition led to numerous masterpieces. Here are ten of Cézanne's most famous paintings you should explore!

The Artist's Father, Reading “L’Événement” (Le Père du peintre, lisant «L'Événement»)

Perhaps one of the most heart-wrenching of the early Paul Cézanne paintings, “L’Événement¨ depicts Cézanne’s father, sturdy and bold, reading a newspaper that championed the Impressionists, with one of Paul’s recent paintings hanging on the wall.

In reality, this scene would never happen, as Paul’s father, Louis-Auguste, thought that art was a frivolous and unrealistic pursuit and was ashamed of his son’s chosen profession. Furthermore, at that time, the Impressionists did not accept Paul.

This painting shows what Cézanne was hoping could be true: that his father and the Impressionists would accept him and be proud of him. It’s also one of his largest paintings ever, underlining the personal importance of the work.

The Murder (Le Meurtre)

As part of the Dark Period, you can see Cézanne’s exploration of darkness in both colour and subject matter. The three anonymous figures convey brutality, the raw and base concepts of the carnal nature of murder.

It’s possible that he was inspired by his friend Émile Zola’s novel 'Thérèse Racquin' which features a heroine who murders her husband.

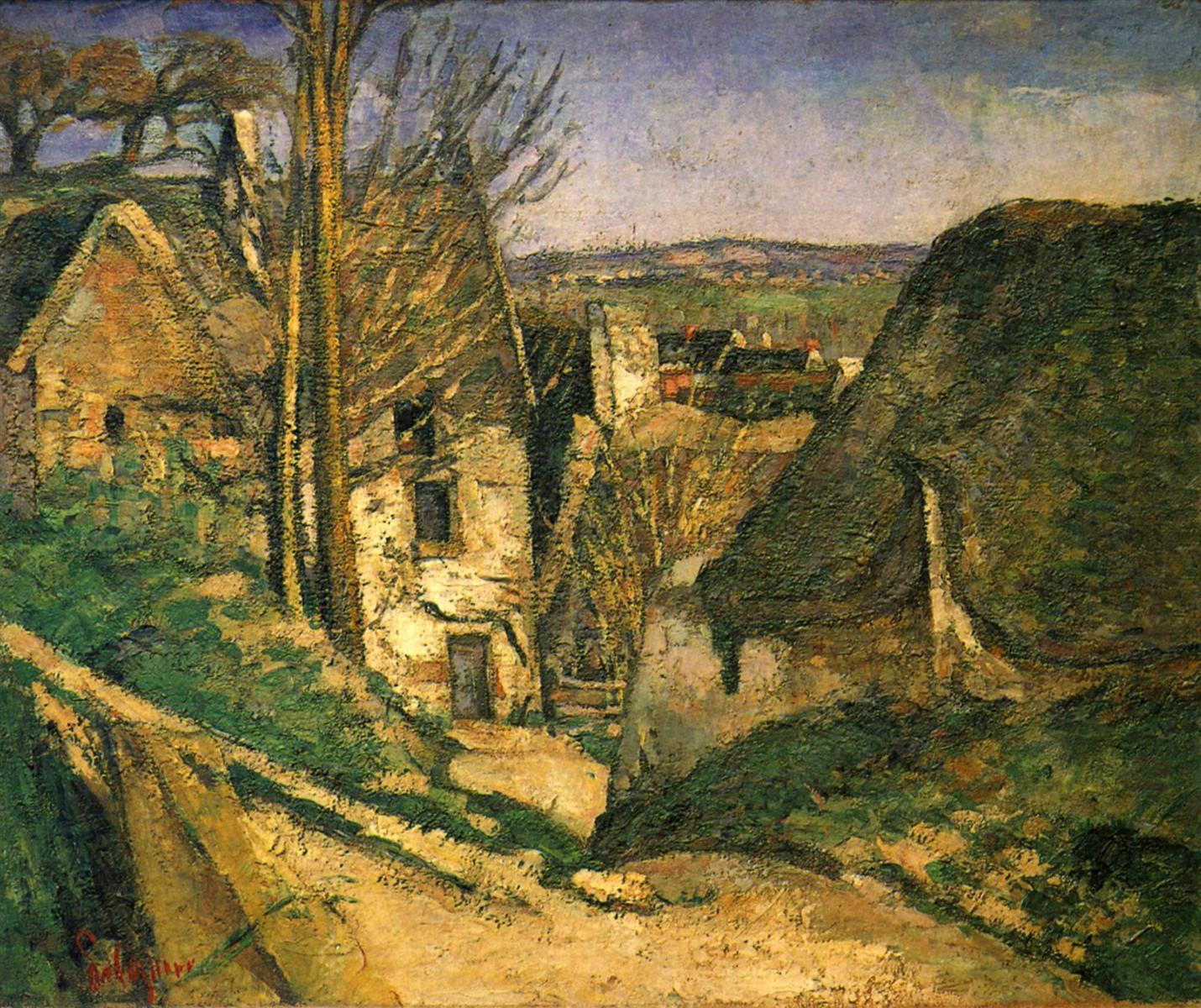

The Hanged Man’s House (La Maison du pendu, Auvers-sur-Oise)

One of the first paintings that Cézanne exhibited (which was poorly received by the public, yet also one of the first paintings to sell), The Hanged Man’s House aka The House of the Hanged Man is a painting depicting a deserted pathway in the small French town of Auvers-sur-Oise.

It’s also one of the few paintings that we can be sure Cézanne was at least mostly happy with the final result.

The name is a farce based on the name of the homeowner – Penn’Du – which sounds like the French word for “hanged man” which is “pendu.” Perhaps Cézanne was running with imagination, saying “this could be the former home of a man who was hanged.” After all, life goes on after such a travesty, and the appearance of the house would not give any hints that anything had happened at all!

Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (Madame Cézanne dans un fauteuil rouge)

There are many Cézanne paintings depicting Madame Cézanne, since she was first a model at the Swiss art school he was attending for classes and then his wife.

Hortense Fiquet was a distinct model because of her large, oval-shaped, round face and forehead. It’s interesting that this portrait stresses these features less than most other portraits of her, which typically feature a harsh centre-part in the hair, enhancing the oval shape.

In 1907, poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a letter describing the painting, saying “the whole picture ultimately holds reality in balance,” praising the use of form and colour to create a coherent balance.

House and Trees (Maison et arbres)

Abandoned houses were common in the countryside at this time, due to the way inheritance laws worked. So, abandoned houses and trees were a subject Cézanne returned to several times. You can see in this image the large crack in one side of the building.

This painting is a prime example of Cézanne’s self-invented painting style called “constructive strokes,” which are the patches of parallel lines together (like a hatch pattern) intended to convey depth and mass without going into the details (which is why his work is Impressionist).

Basket of Apples (Le panier de pommes)

Another repetitive composition among Cézanne and many, many other artists throughout history, painting still-lives of fruits is a common way to practise playing with colour, form, perspective, and other elements of art and artistic style.

This particular example shows how Cézanne played with perspective and translated what can be seen in real life to a canvas, which shows only one angle (rather than real life, where we see with two different angles thanks to having two eyes). Here he plays with how he can get away with putting things together in a disjointed way and still produce a result that looks coherent and sensible.

There’s a reason his works inspired abstraction and Cubism!

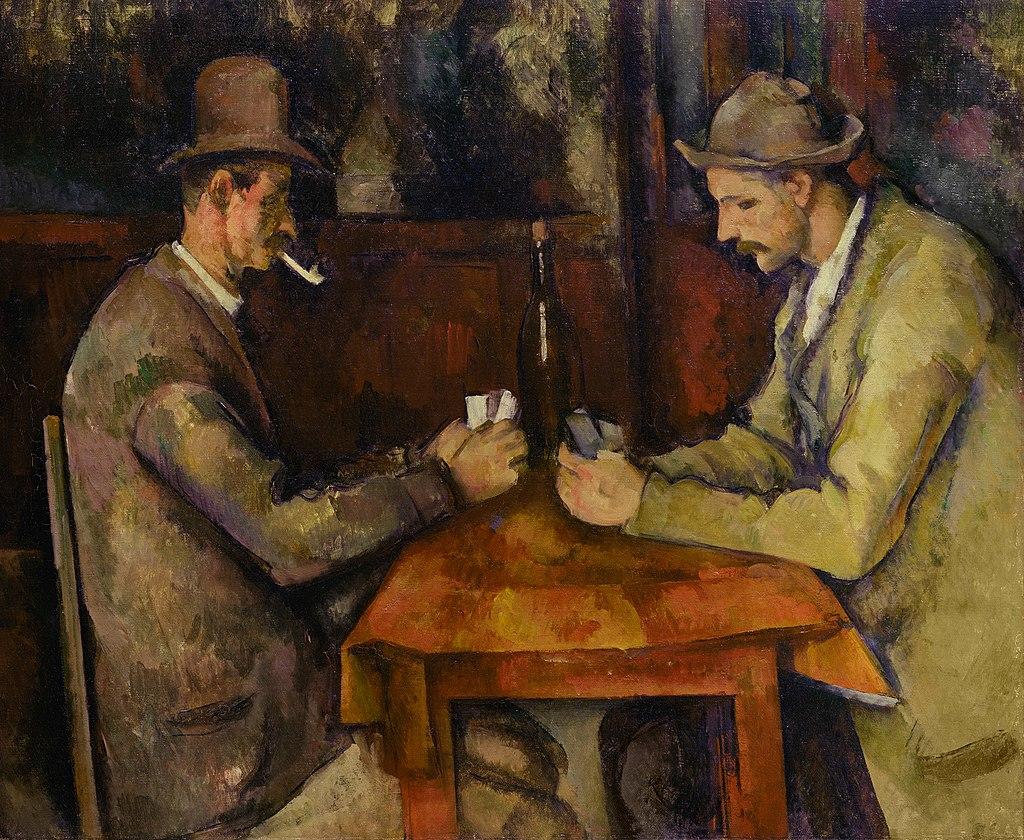

The Card Players (Les Joueurs de cartes)

Cézanne painted a few iterations of this scene throughout his career. An earlier 1893 version of this two-figure scene used darker, cooler, bluer tones. Both versions emphasize and de-emphasize different aspects of the same scene. Depending on personal preference, many people prefer the darker-coloured scene, partly because the figure on the left appears more well-formed.

At the time, painting card players implied that the artist was handling the subjects of vice, sin, and general low-life. Cézanne stepped away from that connotation, portraying two people in a serious and (from what we can see) respectable card game. The depiction of the two men in different clothes and features also shows how the game is an opportunity for people of all sorts to come together as equal players.

Learn how to paint like the greats with painting classes Sydney on Superprof.

Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen From The Bibemus Quarry (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue de la carrière Bibémus)

Yet another recurring theme in Cézanne’s works, he painted Mont Saint-Victoire several times over the years. When viewing the paintings of the mountain in series, you can see each iteration reflecting the style he was using at the time.

Earlier versions of the painting use the more pastel colours of an overcast day or golden hour and showcase the foreground of the small town and trees closer to the artist. In this iteration, wherein the artist is stationed in a quarry rather than at a distance, his colours are more vivid and the mountain appears more towering. In the version following this painting, the foreground is a mish-mash of colours with the mountain being the identifiable object.

The Large Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneurs)

Cézanne’s largest painting, and yet another recurring theme of his works over time, The Large Bathers explores the classical painting theme of female nudity in nature and subdues it to fit the contemporary palette.

The paintings of the old masters like Vecchio’s Bathing Nymphs (c.1525-1528) were well-regarded because they were from a different era, but someone painting such a scene in the 19th century would likely be seen as a deviant. This title may have suited certain painters, but not Cézanne, who had struggled with his own sexuality earlier in life and decided to be less explicit with his work.

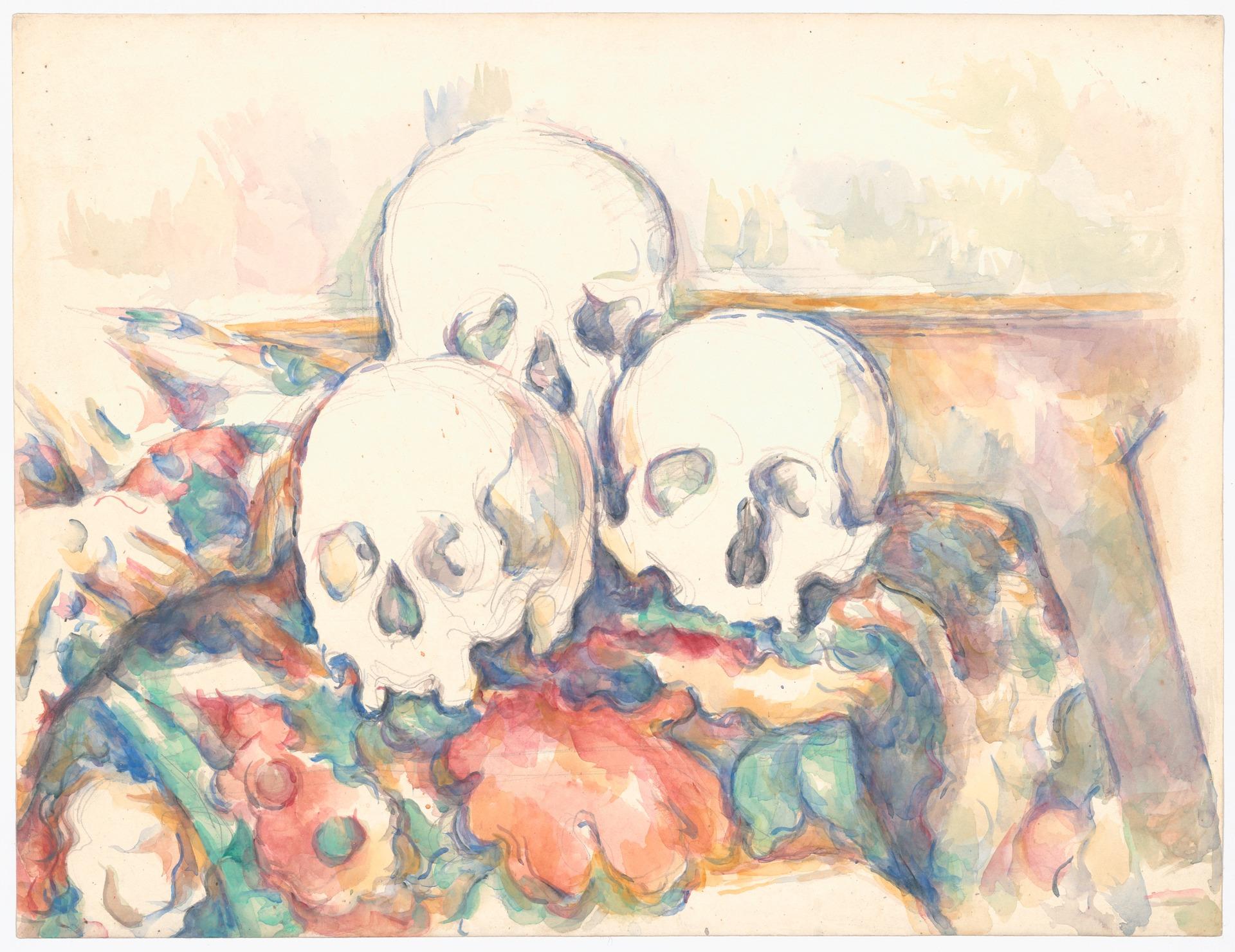

The Three Skulls (Trois crânes)

Cézanne has many famous paintings with skulls, such as Still Life with Skull, Pyramid of Skulls, and another painting titled Three Skulls as well. Depicting memento mori is not a unique motif in many painters’ works.

What makes this painting unique, especially as a Cézanne painting, is that it is a watercolour, which he mostly began after the 1860s. The form and colour are also very different from the majority of the rest of his body of work, as you can see just based on this article! This watercolour painting has an oil-on-canvas counterpart called Three Skulls on a Patterned Carpet.

It’s one of the last paintings he completed before his death in 1906, so it’s fitting that an exploration of mortality is combined with a relatively new artistic style, in a real-life example of endings and beginnings.

Learn about painting techniques with painting classes Brisbane on Superprof.

ontext: The Life of Paul Cézanne

When learning about art, it’s always good to know about the artist’s life as well. Artists reflect their personal experiences into their art; they are inextricably intertwined.

Cézanne’s Early Life

Paul Cézanne was born into a moderately wealthy family on January 19th, 1839, in the French town of Aix-en-Provence. His father, a bank owner, ensured the family was financially comfortable.

At school, he was close friends with the author Emile Zola and the scientist Jean-Baptise Baille. Their friendship and experience would even inspire some of Cézanne's later works.

After completing some law schooling to appease his father, Cézanne eventually studied at the Free Municipal School of Drawing (now the Musée Granet) and moved to Paris in 1861 with Zola.

Being an Artist in Paris

Every painter in Europe at this time had one major goal: to showcase their work at the Salon, the official exhibition that would typically grant featured artists fame and fortune.

However, the Salon typically only showcased the works of students at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the top art school in the city, and Cézanne was not a student.

Instead, he was able to showcase at the Salon des Refusés (literally “exhibition of rejects”), the gallery where Salon rejects were shown. While technically still a great accomplishment, this type of feature had become synonymous with “bad art” for many critics.

Paul Cézanne, unsurprisingly, didn't enjoy the experience and was disheartened and depressed by the poor reception of his art.

The Dark Period (1861-1870)

In addition to being publicly criticised, Cézanne was largely unincluded by his contemporaries, The Impressionists.

Although he was utilising many of the same techniques as the Impressionists, his techniques and personality were different enough that he was ostracized. While the other Impressionists enjoyed using quick strokes and capturing bright, interesting light, Cézanne was exploring dark shadows in a slower, more methodical way. He even began using a palette knife rather than brushes in 1866, which helped lay the foundations for the Expressionist movement.

In both colour and subject matter, Cézanne went through his Dark Period, exploring disturbing themes and even making paintings such as The Murder, The Abduction, and The Rape.

Portrait of a Man (1864), Head of an Old Man (1866), Portrait of Uncle Dominique (1866), The Lion And The Basin At Jas De Bouffan (1866)

The Impressionist Period (1872-1883)

After living in hiding out in L’Estaque to avoid being sent to fight in the Franco-Prussian war (1870-71), Cézanne returned to Paris with his soon-to-be wife, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, whom he had met while painting her as a model at Académie Suisse. They later had one child, also named Paul.

Cézanne became very friendly with the artist Camille Pissarro and the two would regularly paint landscapes in the countryside together. Cézanne's works became much brighter during this time and Pissarro's influence is said to have pulled Paul from his Dark Period.

Cézanne found some support from a few art-lovers, but still had a hard time gaining the public’s admiration. However, the Impressionists finally accepted him and allowed him to showcase his work with them at the Salon!

L’Estaque, Melting Snow (1871), Bouquet in a Delft Vase (1873), The House of Doctor Gachet in Auvers (1873), Cezanne The Orchard (1877), Self-portrait (1879)

The Constructive Period (1883-1895) aka Mature Period

While certain aspects of Cézanne’s life became more stable, others destabilised.

Over the course of this time, he likely suffered from depression (and had for many years, as evidenced by the Dark Period), his father passed away, and he moved in with his mother and sister to get away from his sham marriage (he and Fiquet had fallen out of love).

On top of it all, his dear childhood friend Zola had published a novel titled L'Œuvre which, while he insisted was not based on Cézanne, sure seemed to bear many striking resemblances; and it was not flattering. Hurt by his friend’s betrayal, Cézanne cut Zola out of his life, a break he regretted to his death.

Learn more about art history while learning about artistic techniques with painting classes Melbourne on Superprof.

The happier moments of this time included inheriting a large sum from his father, which meant Cézanne was one of the few artists living comfortably at this time. He also seemed to enjoy some moments with his wife and child despite their troubles.

The art made in this period is Post-Impressionist, still exploring colour and new techniques, some of which helped to establish the style of Cubism. He also met other famous painters such as Monet in this time.

The Gulf of Marseille Seen from L’Estaque (1885), The Boy in the Red Vest (1888), The Card Players series (1890-1895), The Seated Peasant series (1892-1896)

The Synthetic Period (1895-1906) aka Final Period

Cézanne had admired Mont Sainte-Victoire for many years, and during this period, he stayed in a cabin near the mountain and painted many works that would inspire Cubism and Fauvism. After 1890, some of Cézanne's work became darker again, partly due to Zola’s death in 1892.

On the bright side, during this time, Cézanne further perfected his painting techniques and was even finally recognised as a great artist by critics, establishing a grand reputation internationally.

While the fruits of his labour were not realized until just a few years before his untimely death, it is heartening to know that he at least got to experience some of the praise from the public that he had earned after all those years.

Apple Still Life series (1873-1898), The Bathers series (1890-1904), Mont Saint-Victoire series (1867-1906), The Skulls series (1895-1906)

Cézanne’s Legacy

While he found some recognition in his final years, it’s sad that Cézanne passed away before Cubism and abstract paintings were developed. It would have been amazing to see his reaction to the artistic movements his work inspired!

The Spanish artist Pablo Picasso called Cézanne ‘the father of us all’. He heavily inspired painters like Henri Matisse, who was famously a post-Impressionist and the father of Fauvism.

The Salon hosted a retrospective of the deceased artist, despite having regularly rejected his work while alive. Many other exhibitions would also recognise the artist's contribution after his death. Today, many museums around the world proudly display their Paul Cézanne artwork.