The 16th and 17th centuries saw several notable artistic movements in the West, like the Renaissance, Mannerism, and the Baroque period, to name a few. And of course, the names most associated with these movements are typically men: Leonardo Da Vinci, Bronzino, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, and others. But, there was at least one female painter among the Baroque period artists who received recognition: Artemisia Gentileschi.

Early Life

Artemisia was born in 1593 in Rome, Italy, to Orazio Gentileschi and Prudenzia di Ottoviano Montoni. Her father, Orazio, was of Florentine (Tuscan) descent, which was considered very separate from Roman at the time. Artemisia likely held this aspect of her heritage as part of her identity, and it would help her make connections in Florence later in life.

The oldest of four and the only daughter, Artemisia sadly lost her mother when she was only 12 years old (1605).

Orazio was originally a Mannerist painter, but became a follower of Caravaggio, which included the more dramatic chiaroscuro technique and natural motifs.

Orazio taught painting to all of his children, but Artemisia was by far the most skilled and enthusiastic! Although she didn’t receive much of an education in reading and writing, Artemisia was fluent in the language of oil paint.

She debuted her first notable work, Susanna and the Elders, in 1610, at the age of seventeen, to a receptive public who praised the work for its technical mastery.

This scriptural scene was a very popular subject for many Baroque artists, who were almost exclusively men. They tended to portray Susanna as a demure object, usually either unaware of the elders’ leering at her nude form or even receptive and flirtatious towards their attention. Gentileschi painted from a woman’s perspective, showing Susanna’s reasonable and realistic reaction of fear, disgust, and vulnerability at being suddenly cornered while bathing.

Artemisia Gentileschi was taught Caravaggio’s approach to painting, which differed from the common practice of imitating Renaissance art or copying poses from ancient Greek and Roman statues. Instead, Caravaggio hired live models to pose in a room with a high lantern or window, achieving dramatic lighting with highlights and deep shadows, called chiaroscuro. Orazio, a follower of Caravaggio, taught this method to his daughter.

Learn more about Artemisia's history, art history, and art techniques with Brisbane painting classes on Superprof.

The Trial and Becoming an Established Artist

In 1611, Artemisia was raped by Orazio’s colleague, who had been hired to tutor her. The man was taken to trial in 1612 because he refused to marry Artemisia afterwards. Although he was found guilty and sentenced to banishment from Rome for five months, the punishment was never enforced; instead, the man spent less than a year in prison. And if all that weren’t traumatic enough for our heroine, she had been forced to testify in the trial, which lasted seven months, under torture, as was the custom at the time.

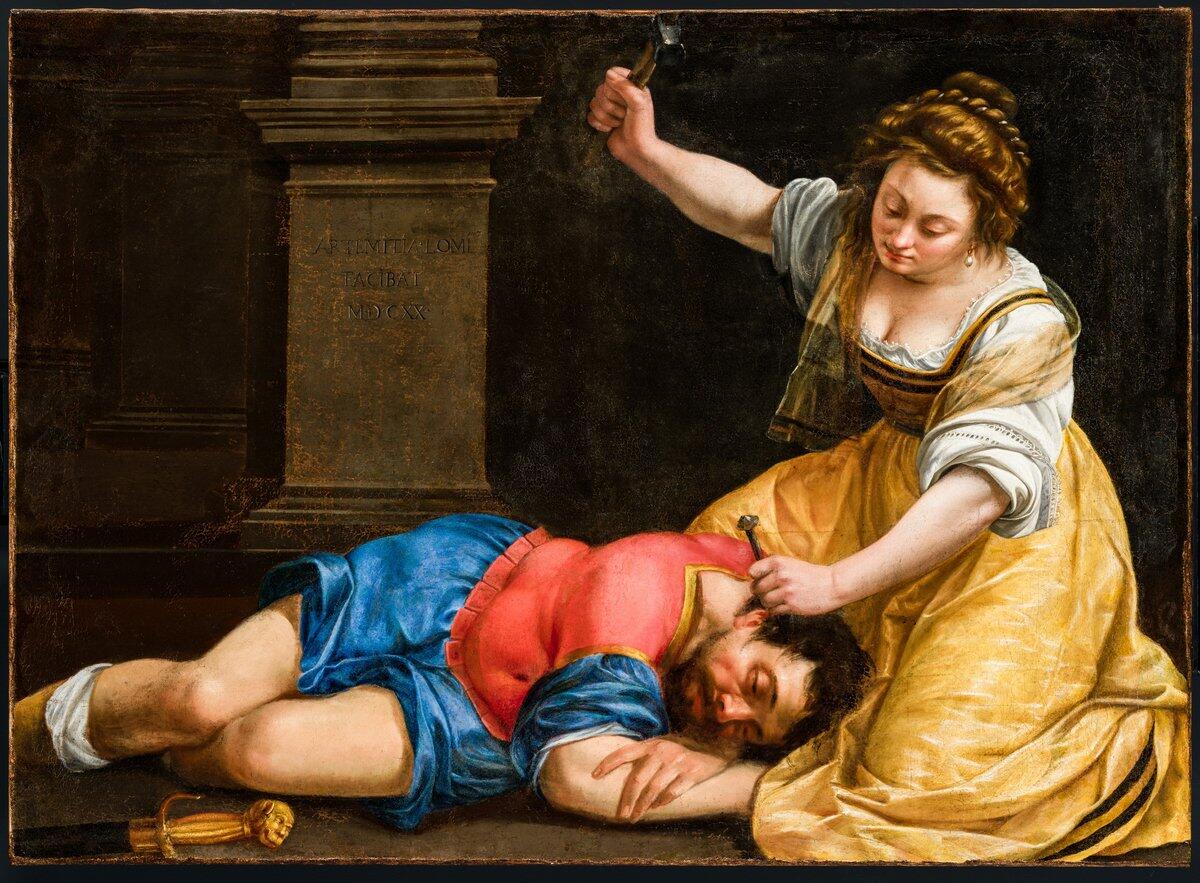

During this time, perhaps as an exercise in catharsis, Artemisia painted Judith Beheading Holofernes (1611-12).

This masterful artwork displays the gruesome murder of Assyrian general Holofernes being decapitated with a dagger by Judith and her maidservant.

Soon after this ordeal, Orazio arranged for Artemisia Gentileschi to marry Pierantonio Stiattesi as a way to move forward with her life. In 1612-13, Gentileschi moved with her new husband to Florence, which was his homeland and her ancestral land. Here, she was able to start building a reputation as a skilled painter.

She set up an art studio in her father-in-law’s house and began creating many of her most famous paintings.

It's an unfortunate theme among many female artists to have complicated relationships with men, even in more modern times, like in Frida Kahlo's case.

Master of Marketing and Networking

Gentileschi’s fame during her lifetime and onward is a monumental feat, especially when you remember that women were treated very poorly compared to men in the art field. To reach the level of renown and secure the high-paying, influential patrons she had, Gentileschi had to have been a very driven, entrepreneurial, and skilful person.

In addition to creating incredible paintings, Gentileschi also had to convince people to look at them and not dismiss them just because they were created by a woman. She was able to do this through her unique style and networking. At the time, any female painters were essentially relegated to only portraiture and still life. Gentileschi’s dramatic historical, Biblical, and allegorical compositions were notable and intellectual, which made her popular in the educated literary circles in Florence. Her early popularity led to her acceptance as the first female into the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy of Arts and Drawing) in 1616, which allowed her to buy art supplies and sign contracts without her husband’s permission. Mary Cassatt is another female artist who had to practice the same tenacity in order to earn her fame.

She secured patronage from the Medici family and Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger, painting Judith and Holofernes (c. 1612–1621) and the Penitent Mary Magdalene (1620–1625) for the former and Allegory of Inclination (1615–17), a ceiling painting, for the latter.

Her renown led her to move from Florence to Rome in 1620, to Venice in 1627, and to Naples in 1630 to procure new clients and make more connections.

Everywhere she went, she integrated herself with literary societies and made acquaintances with influential figures, including the Duke of Alcalá.

To further advertise her profession, Gentileschi signed her paintings with large, noticeable signatures incorporated into the composition (rather than the style we are used to today of a small, often unreadable, signature in the bottom corner).

Perhaps the most business-savvy moves Gentileschi made were her artistic decisions, keeping in mind the client and intended audience.

She frequently included stylistic choices that she thought would be better appreciated by the patron, which sometimes went against what was common for the subject matter, and sometimes meant that she added more risque imagery.

For example, in Mary Magdalene (c. 1620), Gentileschi portrays Mary in a fine satin gown, as if she has just decided to trade in her finery that very moment, and so hasn’t changed into plain clothes yet. Traditional portrayals of the scene show Mary already having shunned her vanity.

But the commissioner of the piece, Maria Maddalena of Austria, enjoyed beautiful things, so Gentileschi wisely decided to dress her version of Mary lavishly for the Grand Duchess of Tuscany’s enjoyment. In other works, Gentileschi included nudity for her male patrons, since she knew catering to the male gaze would get her more work.

🎨 Find painting classes Perth on Superprof.

The other main marketing technique Gentileschi employed was using her own visage in allegorical portraits, advertising her face at the same time as her skills.

Her celebrity status as a sought-after female artist who had broken into the art world caused many people to seek out an Artemisia Gentileschi portrait; people wanted not just a painting by Artemisia in their collection, they wanted a painting of Artemisia.

Painting Biblical Scenes

Common at the time for most artists were paintings depicting scenes from the Bible. What is unique about the time period is that it wasn’t just the wholesome or spiritually uplifting, Jesus-focused scenes; often, paintings displayed scenes we might hardly be familiar with in modern day.

For example, many of the paintings already mentioned are Biblical tales, such as the scenes with Susanna and Judith, as well as Mary Magdalene. Gentileschi often revisited the same theme several times; there are multiple known works depicting Mary Magdalene’s transformation, Judith and her maidservant’s actions surrounding Holofernes, Susanna at her bath, and Madonna and Child. She focused mainly on Biblical heroines who evoked a sense of female capability and strength.

Other Biblical scenes Gentileschi is known for include:

- Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (c. 1623-25)

- Jael and Sisera (c. 1620)

- Nativity of St. John the Baptist (c. 1633-35)

- Esther before Ahasuerus (c.1628-35)

These evocative and technically masterful scenes attracted wealthy patrons who commissioned Gentileschi to recreate their favourites.

Learn about various art techniques with painting courses here on Superprof.

Historical and Mythological Paintings

Gentileschi is also well-known for her scenes depicting Greek and Roman mythology. These scenes were also highly popular, having been the subject of paintings and sculptures for centuries.

- Cleopatra (c. 1633-35)

- Lucretia (1620-21)

- Danaë (c. 1612).

- Venus and Cupid (c.1625-30) and Venus Embracing Cupid (c.1640)

- Aurora (1625-27)

- Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1615-1617)

Just like in her Biblical scenes, Gentileschi focuses primarily on the capable and strong women of history and in mythology. And in the case of Lucretia, women who were wronged and who exercised their agency to decide what happens next.

Many art historians used to sum up Gentileschi’s body of work as mostly being revenge fantasies relating to her rape. While this is likely partly true (especially since many of her portrayals of murdered men are supposedly made to look like her rapist), there is so much more that informed her art.

As mentioned previously, Gentileschi was a master at creating genuinely beautiful and emotive paintings while also tailoring them to the audience and the patron. If many of her patrons also happened to enjoy the emotionally stimulating imagery of men being killed, who was she to deny their requests?

Many women experience society placing unintended messages onto their art, such as Georgia O'Keeffe and her flowers.

Self-Portraits and Allegory Style Paintings

The third main style of painting in Gentileschi’s body of work is allegorical paintings, meaning, paintings that symbolise deeper moral, spiritual, or self-referential ideas. She often used herself as a model for these allegorical paintings, not including much commentary about herself in the composition, and simply using her visage as a model and as a way to advertise her face.

However, one of her most famous paintings is Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura) (c. 1638-39) in which Gentileschi combined a true self-portrait with an allegorical portrait.

Some of Gentileschi’s allegorical paintings are self-referential; they convey information about her as an artist on a metaphorical level. In this time period, it was typical for artists to create such self-portraits according to the Iconologia, a book published in 1593 by Cesare Ripa. The book describes the iconography artists should use to convey certain attributes in an allegorical painting.

On its face, the painting looks like a promotional self-portrait of the artist in action: her gaze is focused on a nondescript canvas, inviting the audience to imagine what Artemisia could create for them, and the dull background conveys that the focus here is the painter.

But, remembering that the Iconologia was in fashion, viewers would have quickly noticed the references that turn the portrait into an allegory: Gentileschi’s black hair is gently dishevelled, showing artistic dedication and passion; her neck sports a gold chain with a mask pendant; and she is holding both a paintbrush and a palette. But the one main element missing from the painting? A cloth gag, which symbolises that the painting is silent. The implication is that the painting is meant to speak volumes and that Gentileschi refused to be silenced as a woman and artist.

Other notable allegorical style Gentileschi paintings include:

- Self-Portrait as a Lute Player (1615-17)

- Self-Portrait as a Female Martyr (c. 1615)

- Allegory of Inclination (1615-17)

A female artist who went a completely different direction with her art is Helen Frankenthaler, who specialised in Abstract Expressionism.

The Life of Artemisia Gentileschi

All while building her successful painting career, Gentileschi also gave birth to four children, only one of whom survived to adulthood. Her surviving daughter, Prudentia, was born in 1618.

She also had a lengthy affair with a nobleman in Florence named Francesco Maringhi around this same time, which her husband, Stiattesi, was aware of. Surprisingly, he allowed the affair, even corresponding with Maringhi through letters. It’s believed that Maringhi financially supported the family, which was much-needed in Gentileschi’s early years before building her reputation and because of Stiattesi’s poor money-handling.

As long as I live I will have control over my being.

Artemisia Gentileschi - Court papers quoted by National Gallery, London, UK

Gentileschi and Stiattesi estranged in 1621, and she raised her daughter while becoming a successful artist and travelling to different cities in search of work.

In 1638, she travelled to London to assist her ill father, who was working there as a painter for the King of England. Sadly, Orazio died in 1639.

Gentileschi stayed in England for a short time, leaving before the civil war started in 1642. It’s believed she returned to Naples and worked until her death. Her exact date of death is unknown, but it’s believed that she was a victim of the plague that infested Naples in 1656.

Gentileschi's legacy has helped many other female artists through time gain their rightly-earned recognition in history.

References

- Artemisia Gentileschi - Paintings, Artwork & Judith. (2019). In Biography. https://www.biography.com/artists/artemisia-gentileschi

- Artemisia Gentileschi was born on July 8, 1593, in Rome and is one of the most distinguished artists of her generation. (n.d.). In Italian Art Society. https://www.italianartsociety.org/2020/07/artemisia-gentileschi-was-born-on-july-8-1593-in-rome-and-is-one-of-the-most-distinguished-artists-of-her-generation

- Athena Art Foundation — In-Depth: Artemisia Gentileschi. (n.d.). In athena art foundation. https://www.athenaartfoundation.org/artemisia-in-depth

- Barrington, B. (2020). The trials and triumphs of Artemisia Gentileschi. In Apollo Magazine. https://apollo-magazine.com/artemisia-gentileschi-london

- Candy Bedworth. (2025). Artemisia Gentileschi in 10 Paintings. In DailyArt Magazine. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/artemisia-gentileschi-in-10-paintings

- Exhibition Artemisia in Paris. (n.d.). In Musée Jacquemart-André. https://www.musee-jacquemart-andre.com/en/artemisia

- Gentileschi Paintings, Bio, Ideas. (n.d.). In The Art Story. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/gentileschi-artemisia

- Meyer, I. (2021). Artemisia Gentileschi Paintings - The Queen of the Baroque. In Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/artemisia-gentileschi-paintings

- Smarthistory. (n.d.). In Artemisia Gentileschi, Conversion of the Magdalene. https://smarthistory.org/artemisia-gentileschi-conversion-of-the-magdalene