Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been denied fundamental rights, recognition, and justice in their own land for much of Australia's history. The Australian civil rights movement challenged this reality. From early protests in the 1930s to recent legal and political milestones, here are the key events, people, and ideas that have shaped the movement.

The Day of Mourning and Early Aboriginal Activism (1930s–1950s)

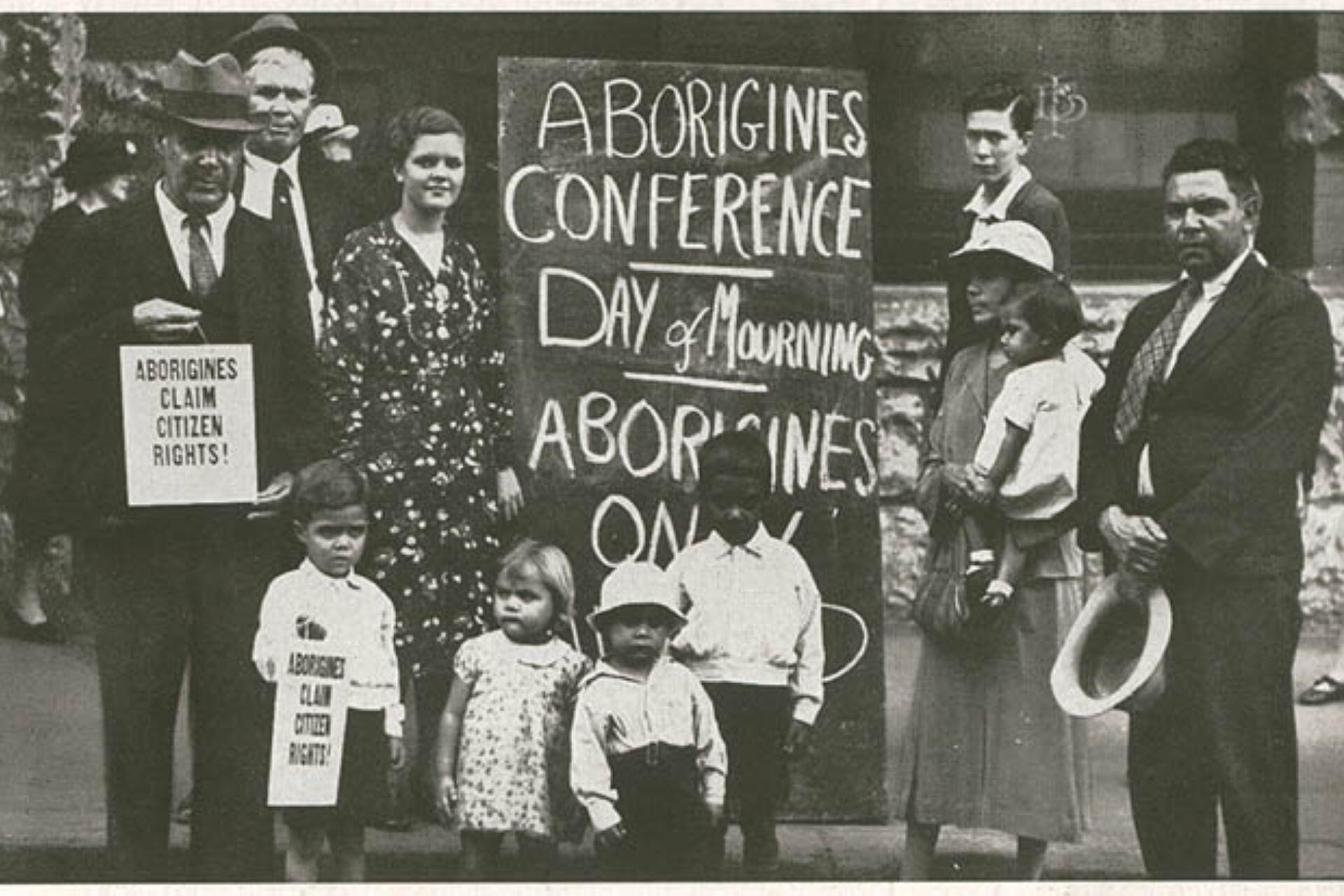

Before civil rights were a national conversation in Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were seeking justice, equality, and recognition. The Day of Mourning, held on 26 January 1938, was one of the most significant early moments in Australian history. Held on the 150th anniversary of British colonisation, Indigenous leaders celebrate this day as a reminder of dispossession, violence, and a denial of fundamental human rights. In contrast, the government celebrated it as a national milestone.

Figures like William Cooper, Jack Patten, and William Ferguson helped organise the Day of Mourning, making it a powerful protest in Sydney. Aboriginal delegates from across New South Wales gathered, demanding full citizenship rights, land rights, and an end to discrimination. Their manifesto called for equal treatment under federal and state laws, better access to education and health services, and a national policy for Aboriginal affairs.

This marked a shift toward national Aboriginal political organisation, with these early activists laying the foundations. The indigenous rights movement asserted that Aboriginal Australians were not just the original people of Australia, but also rightful citizens who deserved justice, dignity, and legal recognition. Despite Aboriginal history stretching tens of thousands of years, they were largely ignored by the federal government at the time.

On 26 January 1938, around 100 Aboriginal leaders and activists, including William Cooper, Jack Patten, and William Ferguson, held a protest in Sydney to condemn 150 years of dispossession and demand full citizenship and equality.

The Freedom Ride and Student Activism (1965)

In 1965, Charles Perkins led a group of university students onto a bus. This bus journey would become one of the most iconic protests in Australian civil rights history. Known as the Freedom Ride, the campaign drew inspiration from similar civil rights actions in the United States. It aimed to expose and challenge the entrenched racial discrimination faced by Aboriginal people in New South Wales.

Organised by Student Action of Aborigines (SAFA), the Freedom Riders travelled through towns like Moree, Walgett, and Bowraville, encountering racially segregated pubs, pools, cinemas, and RSL clubs, despite Aboriginals fighting in both world wars for Australia.

The group staged a protest against the local council's ban on Aboriginal children using the town's swimming pool in Moree. There was a tense standoff, but the council briefly overturned the ban. The moment was broadcast nationally and forced many Australians to confront racism in their own country.

The Freedom Ride revealed to the rest of Australia the injustices and everyday discrimination faced by Indigenous peoples. It also helped spur the Aboriginal rights movement, especially among younger Australians. Through it, Charles Perkins became a prominent voice in Aboriginal activism. He laid the groundwork for further civil and human rights reforms in the following decades.

The 1967 Referendum and Federal Recognition

The 1967 Referendum was a significant milestone for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights. It was held on 27 May 1967 and asked Australians whether two key sections of the Australian law should be amended to recognise Aboriginal people better. The first change would enable the federal government to enact laws for Aboriginal people, and the second would include them in the national census.

Before the referendum, Aboriginal people weren't included in the census. The federal government had no constitutional power to legislate for them, so individual state governments had to do so. This ultimately resulted in discriminatory or neglectful policies. The referendum took place following years of advocacy and public awareness campaigns led by organisations like the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI).

90% of Australians voted "Yes", making it one of the most unified votes in Australian referendum history. The vote didn't fix systemic inequality, but it was a powerful symbolic victory, marking a shift in public sentiment. It gave Indigenous Australians constitutional recognition and paved the way for further legal and political action. The 1967 Referendum also granted the Commonwealth government greater authority to take an active role in Indigenous affairs.

of Australians voted "Yes" in the 1967 referendum. The highest level of support ever recorded for a constitutional change.

Land Rights, Protests, and the Tent Embassy (1970s–1980s)

Following the 1967 Referendum, a growing push for land rights, political recognition, and sovereignty emerged for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the 1970s and 1980s. Constitutional recognition was a step forward, but it didn't fix the more profound injustices faced by First Nations Australians, especially when it came to land dispossession and self-determination, which had been happening since way before Federation.

In 1972, a powerful act of protest took place outside of Parliament House in Canberra: the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. This started as a beach umbrella on the lawns; the embassy was a response to Prime Minister William McMahon's refusal to recognise Aboriginal land rights. It soon became a permanent and internationally recognised symbol of Indigenous protest, calling attention to the issues of land, justice, and political autonomy.

The Tent Embassy demanded legal ownership of land, mining rights, and compensation for land loss. It was removed and reinstated several times over the years, but it remains a significant site of protest and resistance that draws attention to historical and contemporary injustices.

At the same time, the land rights movement grew stronger. The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 recognised Aboriginal claims to traditional lands. Passed under the Whitlam and later Fraser governments, this was the first legislation of its kind and set a precedent for further state and federal initiatives.

Protest, legal action, and activism at the time became more organised and vocal. Groups like the National Aboriginal Consultative Committee and the National Aboriginal Conference have helped drive political engagement. Public demonstrations, such as Invasion Day protests, land marches, and community rallies, have ensured that Indigenous issues remain part of the national debate.

Mabo, Native Title, and Legal Recognition (1990s)

The Mabo case in the 1990s was central to the struggle for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights. This was a historical legal challenge that overturned the false and damaging doctrine of terra nullius, the idea that Australia was empty land before British colonisation.

Eddie Koiki Mabo, a Meriam man from the Torres Strait, led the legal fight to have his people's traditional ownership of lands on Murray Island recognised under Australian law. After a decade-long battle, the High Court of Australia ruled in 1992 that Indigenous land rights preexisted colonisation and continued to exist in many parts of the country. This decision became known as the Mabo decision.

The ruling had a profound impact. For the first time in Australian law, it acknowledged that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had lived in Australia for thousands of years with their own rules and customs, and their land rights survived colonisation.

The federal government passed the Native Title Act 1993 under Prime Minister Paul Keating. A legal process was established that allowed Indigenous peoples to claim native title to their traditional lands by demonstrating an ongoing cultural connection and proving that the land hadn't been sold or legally extinguished.

The Native Title system was a significant step forward, but it was also complex, limited, and often adversarial. After all, Indigenous communities had to navigate a Western legal framework. However, the Mabo decision and the Native Title Act marked a turning point, as they embedded Indigenous rights into Australian law, reshaping the national conversation around history, justice, and reconciliation in the country.

26 January 1938

Day of Mourning

First national protest by Indigenous leaders calling for justice amid Australia Day celebrations.

1965

Freedom Ride

Led by Charles Perkins, students exposed racial segregation across NSW towns, sparking national awareness.

27 May 1967

Referendum Passed

90.77% voted to include Indigenous Australians in the census and give federal government law-making power for them.

26 January 1972

Aboriginal Tent Embassy Established

Protest in Canberra demanding land rights and political autonomy, becoming an enduring symbol of Indigenous activism.

1992–1993

Mabo Decision and Native Title Act

The High Court overturned terra nullius and the Native Title Act formalised Indigenous land rights.

Reconciliation, Apologies, and the Uluru Statement (2000s–Present)

During the 21st century, the national conversation around reconciliation, recognition, and justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples has deepened. In the earlier decades, the focus was on civil rights and land recognition. More recently, efforts have focused on truth-telling, healing, and constitutional change.

2008 was a key moment. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd delivered a formal national apology to the Stolen Generations, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families under government policies. This powerful address to Parliament acknowledged the suffering, trauma, and injustice that had been caused.

Beyond apologies, Indigenous Australians continued their calls for structural change. In 2017, the Uluru Statement from the Heart was issued by Indigenous delegates across the country. The statement was a strategic call for three things:

The Uluru statement was widely supported by Indigenous communities. However, political action has been slow and divisive. In 2023, a referendum on establishing the Voice to Parliament was held but not passed. The movement for justice and reconciliation remains strong and Indigenous leaders, communities, and allies continue to advocate for land rights, cultural protection, health equity, and political empowerment.

Legacy and Continuing Struggles

The Aboriginal civil rights movement in Australia has made advancements in decades since the Day of Mourning. However, the struggle for justice, equality, and recognition is far from over. The movement has found increased visibility, political participation, and cultural pride for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, but disparities remain.

Despite postwar immigration policies to make Australia a more multicultural society, Indigenous Australians are among the most disadvantaged groups in the country. Life expectancy, health outcomes, educational attainment, and incarceration rates are examples of inequality. Systemic racism, intergenerational trauma, and the legacy of colonisation still shape daily life for many communities. These aren't historical issues. For many, they're lived realities.

Summarise with AI: