Australia's post-war migration policy was one of the most ambitious in history. It took Australia from a sparsely populated British outpost into a vibrant multicultural nation. Bringing in migrants boosted the economy, strengthened defence, and fuelled national development, the country welcomed millions of newcomers, reshaping its society, suburbs, and identity in the process.

Post-War Australia and the Call to "Populate or Perish"

After the Second World War, Australia faced a different kind of struggle. It had endured two global conflicts since the Federation, but vulnerabilities were also exposed during periods of peace. The country's small population was spread across a vast landmass.

In 1945, Prime Minister Ben Chifley's government adopted a new approach for post-war Australia: a large-scale immigration programme to strengthen the nation's economy, defence and workforce. Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell's phrase "populate or perish" summed up the situation reasonably well. The argument was that the country needed to increase its population through natural growth and mass migration. A larger, more diverse workforce would drive economic development, boost national defence capabilities, and help Australia grow as a presence in international affairs.

The policy enjoyed support. War had heightened awareness of how vulnerable Australia could be to external threats, and the stage was set for a significant social transformation that would mark Australian history, reshaping society, culture, and the economy.

Between 1945 and 1965, about 2 million immigrants arrived in Australia under the “Populate or Perish” policy, reshaping the nation’s demographic and cultural landscape.

Why Did People Migrate to Australia After WWII?

During WWII, millions of people across Europe had been displaced. Homes had been destroyed, and economies were reeling from the conflict's devastating effects so emigration was a way to get a fresh start. Though Australia had participated in the war, it boasted vast, open spaces and a growing economy. It was actively welcoming immigrants, making it an attractive destination. The Australian government sought migrants to strengthen national defence, boost industrial labour, and fuel economic development.

The “populate or perish” phrasing and policy may have sounded a bit dramatic, but it was a national necessity. There were agreements signed with Britain and later other European countries to encourage immigration. Former soldiers, refugees, and families looking for safety and stability after war came to Australia. Others chose to come because of good wages, stable employment, and a better future for their children in a peaceful country.

It wasn't just the pull of Australia, though. Post-war Europe was facing food shortages, housing crises, and political instability. Large numbers of people left nations such as Italy, Greece, and the Netherlands to escape poverty and seek opportunities abroad. They couldn't see a way to stay where they were, and Australia was there with open arms, a willing host with assisted travel schemes and settlement support. Australia was a beacon of hope for those trying to rebuild their lives after the Second World War.

Post War Migration to Australia: Assisted Schemes and Displaced Persons

The Australian government launched a series of assisted migration programmes. The Assisted Passage Scheme for British migrants, known as the "Ten Pound Pom" programme, allowed adults to migrate to Australia for a fare of £10, with children travelling for free. The migrants were required to remain in the country for at least two years or repay the cost of the journey.

British migrants took advantage of the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme ("Ten-Pound Poms") between 1945 and 1972.

Initially, Australia focused on attracting people from Britain, likely due to its historical connections with the nation. The demand for labour quickly outstripped the available supply, so agreements were made with other European nations. In 1947, Australia became a signatory to the International Refugee Organization programme. This brought tens of thousands of displaced persons from war-torn countries like Poland, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine, and Czechoslovakia who'd been living in refugee camps across Europe since the end of the war.

When they arrived, the migrants were sent to reception and training centres, such as the Bonegilla Migrant Reception Centre in Victoria. They received basic English lessons and were matched with jobs in manufacturing, construction, or rural work. The schemes were a key part of the Commonwealth's post-war economic and social development goals, a steady flow of workers to build infrastructure and expand cities like Sydney and Melbourne.

Who Migrated to Australia After WWII?

The first wave of post-war migration to Australia was primarily comprised of British arrivals under the assisted passage scheme. The "Ten Pound Poms" were seen as compatible with Australian society because of the country's history. Migrants within the Commonwealth were initially preferred, with many settling in major cities such as Sydney and Melbourne, as well as in regional centres where labour shortages allowed them to find employment.

As the demand for workers increased, Australia opened its doors to a broader range of migrants. Many came from southern and eastern Europe. Italians, Greeks, Dutch, Germans, Maltese, and later Yugoslavs. These migrants were often escaping economic hardship, political instability, and the devastation of World War II.

Thousands of men and women from the Baltic states and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe came under the International Refugee Organisation's Displaced Persons Programme. Many arrived with no family ties in Australia, but they played a vital role in the nation's reconstruction, contributing to projects such as the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. This would lead to a shift in Australia's social fabric, ultimately creating the multicultural nation that emerged in the late 20th century, though the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples still seemed to be left from much of the narrative.

Life for Migrants in Post-War Australia

For migrants, post-war Australia presented both opportunities and challenges. After long journeys by sea, newcomers arrived at reception centres and received basic English instruction, health checks, and job placements.

Some were sent to rural settlements to work in agriculture. Others went to expanding cities like Sydney and Melbourne, where they joined the manufacturing and construction industries. Work was physically demanding, with many men working on major infrastructure projects, such as roads, dams, and the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. Women worked in textile factories, hospitals, and domestic service.

While the pay was better than in much of Europe, many migrants faced language barriers, cultural isolation, and hostility from parts of the Australian public still influenced by the White Australia Policy, which would require an extensive civil rights movement to dismantle.

Migrant communities established strong networks with churches, cultural associations, and ethnic clubs, which provided social support. Migrants in Australia preserved their languages, traditions, and even their home country's food. Over the years, these communities became a key part of Australian society, enriching the nation's cultural landscape and changing public attitudes towards immigration and diversity.

The End of the White Australia Policy and the Rise of Multiculturalism

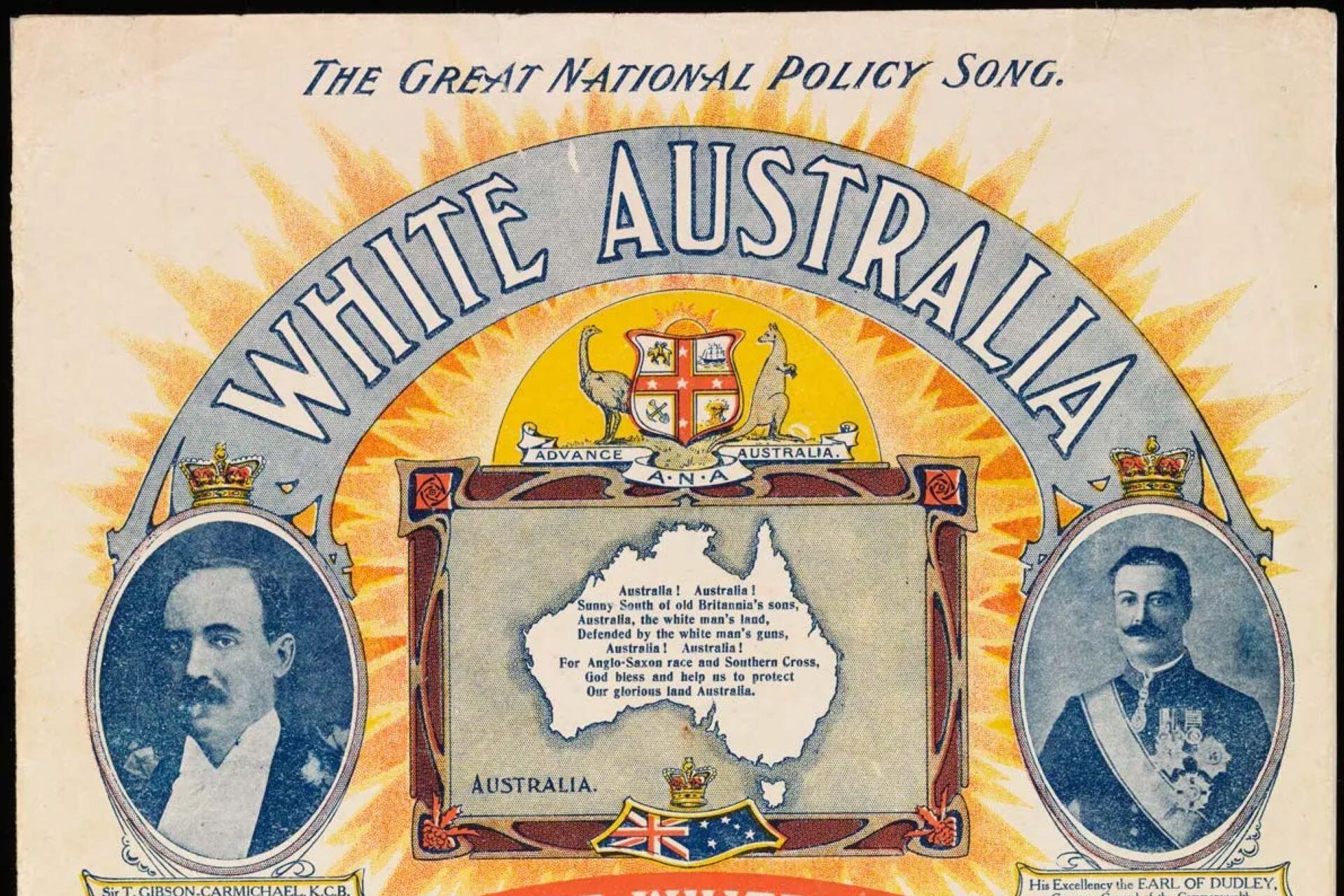

When post-war immigration to Australia started in 1945, it was under the White Australia Policy. This favoured migrants from Britain and other European countries. Some non-European arrivals were permitted in some instances. Still, the policy largely excluded people from Asia and other parts of the world.

By the late 1960s, the Australian government, under both Liberal and Labour leadership, began dismantling the policy. Growing diplomatic engagement with Asian neighbours and a recognition of the valuable contributions of non-European migrants already in Australia. In 1973, the Whitlam government formally ended the White Australia Policy. It was replaced with a commitment to non-discriminatory immigration criteria.

From there, the nation embraced an official multicultural policy, recognising that migrants can maintain their cultural heritage while also participating in Australian society. This shift expanded the diversity of immigration in Australia. It signalled a broader change in the country's identity: a modern, outward-looking society enriched by diverse cultures.

1945

“Populate or Perish” Launch

Government begins mass migration drive to populate Australia for defence and development.

1947–1954

Refugees Arrive through IRO

Over 182,000 displaced Europeans were sponsored by the International Refugee Organization to resettle in Australia.

1958

Migration Act Reforms

The dictation test is abolished, enabling entry based on skills and contribution initiating broader immigration.

1959

Australia Reaches 10 Million

Accelerated population growth helped push the population to 10 million.

1973

End of White Australia Policy

Legally dismantled, replaced by criteria- and contribution-based immigration, paving the way for modern multiculturalism.

Economic and Social Impacts of Post-War Immigration

The large-scale post-war migration to Australia changed the nation's economy and society. The influx of migrants provided the required labour for rapid industrial growth. Both skilled and unskilled workers expanded manufacturing output, supported the development of new housing around cities, and played a vital role in the long post-war economic boom that Australia enjoyed for decades.

Immigration also reshaped the country's demographic profile. British, southern European, and later Asian and Middle Eastern migrants came with languages, religions, cuisines, and traditions, which challenged the earlier notions (and policies) of a homogenous Australian society. With it, public attitudes shifted, with multiculturalism being seen as part of the national identity.

Migration also strengthened Australia's international ties, especially with the countries that had sent large numbers of migrants. Diplomatic engagement extended beyond just Britain, and while tensions flared during economic downturns or housing shortages, the overall legacy of post-war immigration to Australia was a more dynamic, open, and outward-looking nation.

As of June 2024, 31.5% of Australians or 8.6 million people, were born overseas, the highest level since the 19th century.

Legacy of Post-War Migration in Modern Australia

Post-war immigration has left a permanent mark on Australia. Its place in the world and its society have been transformed by it, and what may have started as a government strategy to boost the postwar population and strengthen defence has become part of the nation's fabric.

By the early 21st century, Australia had become one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world, with over a quarter of its population born overseas and many others the children and grandchildren of post-war migrants.

Major cities can see this in the communities, neighbourhoods, and festivals celebrating Greek, Italian, Vietnamese, Lebanese, Chinese, and other cultural traditions. In Australian universities, workplaces, and public life, diversity and multiculturalism aren't just a policy, but an integral part of Australian identity.

This approach also set a precedent for humanitarian and skilled migration policies. It shaped how economic needs, social cohesion, and international responsibilities are handled. Debates over migration levels and integration will continue indefinitely, as they do everywhere. Still, Australia is no longer a British outpost, and that's primarily due to the contributions of people from all over the world.

Summarise with AI: