Every second of every day, and even as we sleep, particles move through our bodies via two types of systems. Active and passive transport move molecules either against or along concentration gradients. A concentration gradient is a gradual change in a substance's concentration, usually across a semipermeable membrane. How and why does this transport happen, and what are those systems?

What to Know About Active and Passive Transport

- Active transport: molecules require energy to travel against their concentration gradient.

- Passive transport: molecules travel along their concentration gradients, needing no energy.

- Transport proteins always feature in active transport. They may not be present in passive transport.

- Transport is vital in nutrition uptake and waste elimination, to regulate the cellular environment, and for many other functions.

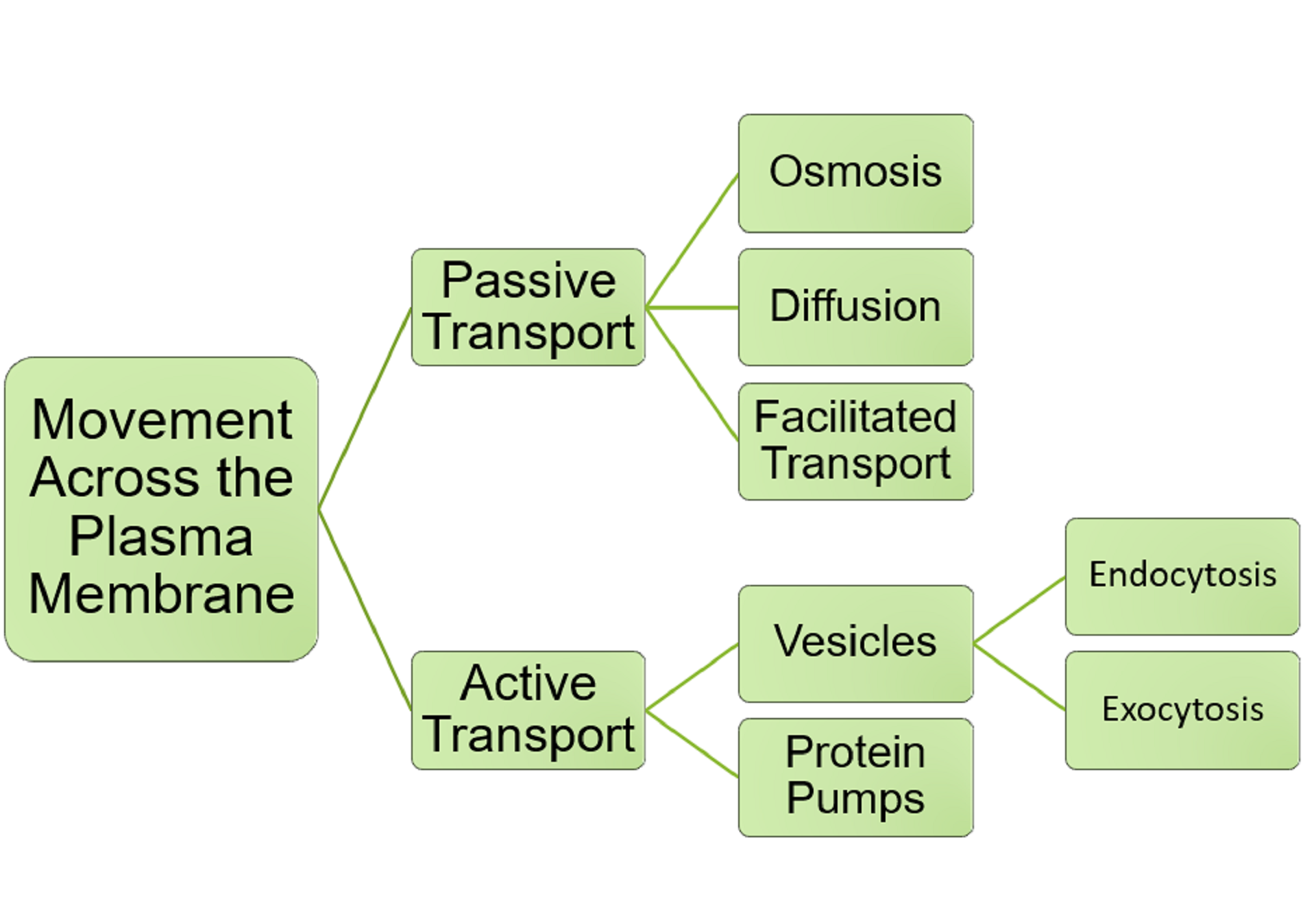

What is Passive Transport?

Passive transport describes molecules moving across a membrane, from a high concentration area to an area of lower concentration. Passive transport relies on the molecules' natural tendency to spread out, to create an even distribution (equilibrium) throughout the cell.

Two factors drive passive transport:

1. concentration gradients.

2. The 2nd law of thermodynamics.

Passive transport sounds like a simple concept. It goes with the flow, as it were, and requires no energy. Don't let those qualities fool you, passive transport comes in four varieties.

Diffusion plays a major role in biological systems. However, its work isn't limited to biology. Across industries, including food production, we see principles of diffusion in action.

Passive Transport Examples

Despite their broad application, we limit our examples of passive transport and diffusion1 to biological systems. Fortunately, examples abound.

Kidney function is a prime example of filtration. Within that organ, the glomerulus, an enclosed network of capillaries, allows water, glucose, and other ions to pass through its pores. Larger molecules, such as albumin and other proteins, are too big to filter through.

This is a symptom of kidney stress. If your kidneys allow larger protein molecules through, it could mean anything from simple dehydration to kidney damage due to disease.

Osmosis is how cells maintain their structure and function. Cells maintain optimal function in isotonic environments, meaning that water movement is balanced in both directions. Osmosis is a vital process in nutrient uptake and waste removal, too.

Facilitated diffusion is a more specific process. Unlike random diffusion, which seeks to balance solute concentrations in all directions, facilitated diffusion targets specific entry channels. Polar molecules (ions, glucose, etc.) give us the best examples of this process. For instance, glucose enters the cell via glucose transport (GLUT) proteins embedded in the cell's membrane.

By contrast, simple diffusion needs no elaborate setup; it's how small molecules move across membranes. Nonpolar molecules, such as CO2 and oxygen, flow via simple diffusion. Our lungs present the best example of simple diffusion. Those organs' alveoli diffuse oxygen into the bloodstream and allow carbon dioxide from the blood into the lungs for exhalation.

What is Active Transport?

If we can (simplistically) describe passive transport as going with the flow, then active transport must mean going against the flow.

Imagine you're in a crowded area, like a concert hall or a football stadium. Everyone's streaming in, trying to get to their seat before the action starts. But you need a bathroom in the worst way.

To cut through the crowds, you need more than a few 'excuse me's and the ability to make a path for yourself through the masses. You might also need a bit more leg power to walk up the ramps - or control to walk down ramps, out of the arena.

That analogy helps us visualise active transport mechanisms. For molecules to move against their concentration gradient, they need a bit of extra power. That power comes in two forms.

Primary active transport

The molecule uses ATP for transport energy.

Secondary active transport

The molecule uses electrochemical gradient energy.

What are those forms of energy? It seems we have some defining to do.

ATP: stands for adenosine triphosphate, the cells' main energy-carrying molecule.

Electrochemical gradient energy: the potential energy stored across a membrane3, typically a byproduct of primary active transport.

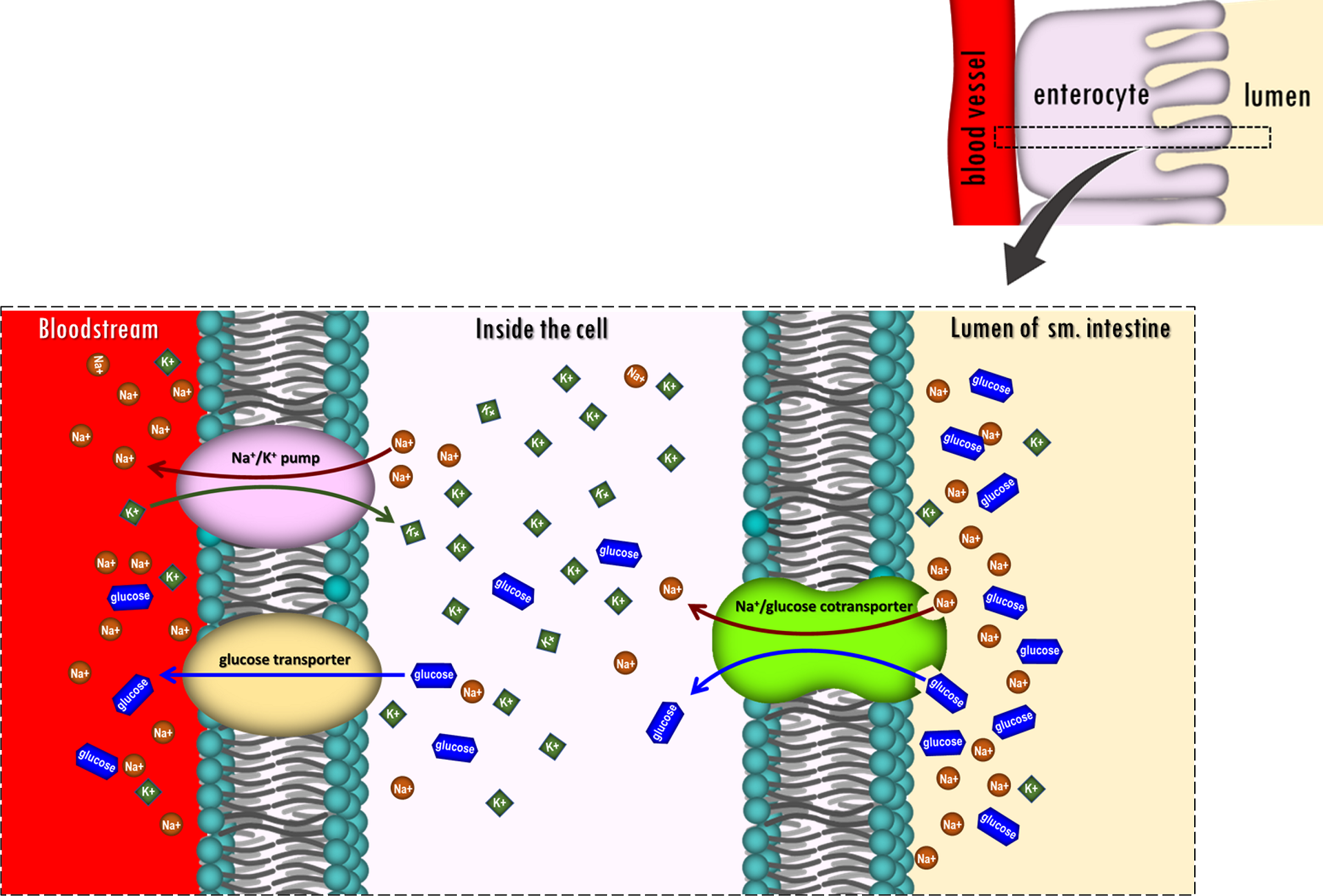

In both cases, active transport relies on specific proteins found in the membrane, or on pumps. Those pumps bind to specific molecules and change their shape to transport them.

Cells rely on active transport for nutrition accumulation, particularly amino acids and glucose. This transport system is also vital to maintain ion concentrations and remove waste.

Active Transport Examples

Photosynthesis might be the most recognised example of active transport. Plants use light energy to transport nutrients and to pump protons across cell membranes. But we find many more examples of active transport in biological systems.

The heart is a delicate organ that requires balanced ion levels. Cardiac muscle cells feature a sodium-calcium exchanger that transports three sodium ions into the cell while moving one calcium ion out. The sodium gradient powers this process.

In similar fashion, cells' sodium-potassium pumps use ATP to move three sodium ions out of cells while feeding two potassium ions into it. This exchange is vital to maintain cells' membrane potential.

This describes the electrochemical gradient energy mentioned above.

Glucose transport in the kidneys and small intestine gives us a prime example of secondary active transport. Glucose symporters4 transport two sodium ions along their gradient while simultaneously moving one glucose molecule into the cell, against its gradient.

Active and Passive Transport: Key Differences

Already, we've laid out many differences, but it might be a bit much to note them all as you read. This chart lays out those differences side by side. You might clip and save it for easy reference.

| 📐Aspect | 🏃♀️Active transport | 💺Passive transport |

|---|---|---|

| Role | Accumulate nutrients and other essential molecules, even when concentrations are low. | Maintain equilibrium across membranes, of gases, water, and small solutes. |

| Energy requirements | Needs energy | Does not require energy. |

| Direction of movement | Moves against concentration gradients. (low concentration to high concentration movement) | Moves along concentration gradients. (high concentration to low concentration movement) |

| Transport proteins | Always involves substance-specific carrier proteins. | May use transport proteins. |

| Selectivity | Always selective | Facilitated diffusion is selective. Simple diffusion is not selective |

| Speed | Generally faster | Typically slower, especially protein assisted transport. |

| Factors that act on the process | Temperature, oxygen levels, and metabolic inhibitors | Only protein-based transport may be affected by temperature. |

Active and Passive Transport in Cellular Function

Now, with the aspects of active and passive transport clear and key differences outlined, we can talk about the importance of these systems.

Nutrient Uptake and Waste Removal

Amino acids, glucose, and ions all travel into cells via active and passive transport. Larger (or polar) molecules typically rely on facilitated diffusion to make their way into cells. This is one of facilitated diffusion's primary functions. When nutrient concentrations outside the cell are lower than inside, active transport kicks in to make sure the cells stay replete.

Waste substances such as carbon dioxide and urine prefer passive transport across membranes. For example, as blood returns to the lungs, CO2 diffuses through the alveoli for exhalation.

By contrast, polar or larger waste molecules require active transport, a process called exocytosis7. This process packages waste into sacs (vesicles), which fuse with the cell's membrane. The sacs' contents are then released outside the cell.

Signal Transduction

Most of the population knows that cells receive and send signals throughout our bodies - our muscles and organs. They don't do so solely on electrical impulse. They're responding to external stimuli, such as those from hormones and neurotransmitters. This is a three-part process:

Reception

The signalling molecule binds to its specific receptor.

Transduction

A molecular sequence converts the signal into an intracellular response.

Response

The expression of change (in gene expression, cell division, enzyme activity, etc.).

Potassium, calcium, and sodium are integral to the signal transduction process. Active transport is vital to maintaining those ions' gradients5. Dysregulated transport or signal transduction may cause neurological disorders, cystic fibrosis and other diseases, and even cancer.

Maintaining Homeostasis

Homeostasis is necessary for life.

Gerald G. May, psychiatrist and theologian

By definition, homeostasis is the maintenance of metabolic equilibrium within an animal's system. As the previous segment informed us, a dysregulated system could lead to disease, incapacity and, eventually, death. So, our cells (and we) have a great interest in maintaining homeostasis.

Active and passive transport are indispensable in maintaining homeostasis. Active transport ensures our cells take up and accumulate nutrients and ions, and expel waste. Passive transport maintains the cellular environment.

The science and medical communities are sounding the alarm ever louder over modern food choices, as they tend to disrupt homeostasis.

Maintaining homeostasis includes what we put into our bodies, as studies show6. Disrupting it threatens the stability of the environment needed to sustain life.

References h2 title

- Singh, Anjali. “Passive Transport: Types and Examples.” Conduct Science, 28 Mar. 2022, conductscience.com/passive-transport/. Accessed 22 Jan. 2026.

- Godfrey, Harry. “Understanding Osmosis in Biology: A Clear Definition and Key Concepts.” Thedegreegap.com, 2025, thedegreegap.com/understanding-osmosis-in-biology-a-definition. Accessed 22 Jan. 2026.

- LibreTexts. “5.10: Active Transport - Electrochemical Gradient.” Biology LibreTexts, 10 July 2018, bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_(Boundless)/05:_Structure_and_Function_of_Plasma_Membranes/5.10:_Active_Transport_-_Electrochemical_Gradient. Accessed 22 Jan. 2026.

- Fiveable. “Symporter Definition - General Biology I Key Term | Fiveable.” Fiveable.me, 2025, fiveable.me/key-terms/college-bio/symporter. Accessed 22 Jan. 2026.

- James, Dr LuÃsa. “Cell Membrane Transport and Signal Transduction: Passive and Active Transport.” Journal of Biochemistry Research, vol. 6, no. 2, 28 Apr. 2023, pp. 26–28, www.openaccessjournals.com/articles/cell-membrane-transport-and-signal-transduction-passive-and-active-transport-16348.html, https://doi.org/10.37532/%20oabr.2023.6(2).26-28. Accessed 22 Jan. 2026.

- Li, Yiping, et al. “Ultra-Processed Food Intake Is Associated with Altered Glucose Homeostasis in Young Adults with a History of Overweight or Obesity: A Longitudinal Study.” Nutrition & Metabolism, vol. 22, no. 1, 10 Nov. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-025-01036-6. Accessed 22 Jan. 2026.

- Diffen. “Active and Passive Transport - Difference and Comparison | Diffen.” Diffen.com, Diffen, 2019, www.diffen.com/difference/Active_Transport_vs_Passive_Transport. Accessed 22 Jan. 2026.

Summarise with AI: