Magnetism refers to the force exerted by magnets when they attract or repel each other. Electromagnetism is the interaction between electric currents or fields and magnetic fields. Together, they form the foundation for many modern technologies, including electric motors, generators, and communication systems. Before we explore magnetism and electromagnetism, take a moment to master these terms.

| 📑Term | 📖Definition | 🏭Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetism | The force magnets exert. | Everything from computers and headphones to cars and industry. |

| Paramagnetism | The weak level of magnetism in substances that have magnetic potential. they become magnetised from outside sources. | Where weak magnetic applications are needed, such as medical equipment, maglev trains, and sensitive laboratory equipment. |

| Diamagnetism | Atomically stable materials with mostly paired electrons. | In medical equipment, superconductors, and high-speed trains. |

| Ferromagnetism | Substances that can become magnets when subjected to a magnetic field. | These magnets enjoy the broadest application, from headphones and credit card magnetic strips to automotive and industrial applications. |

| Magnetic field | The distribution in a space that allows for magnetic force. | Every application that uses magnets of any type depends on the magnet's magnetic field. |

| Magnetic strength (magnetic force) | The intensity of a magnetic field at a specific point | Intensity can vary depending on where the magnet is applied. |

| The right-hand rule | The way to determine magnetic force's direction. | Typically used in laboratory settings. |

| Electromagnetism | The interactions between electrically charged particles and their associated electric and magnetic fields. | Wide usage in industry, technology, and household applications. |

| Solenoid | A type of electromagnet that generates a controlled magnetic field. | Wide usage in industrial, mechanical, automotive and household settings. |

| Faraday's Law | A law that states any change in the magnetic environment of a coil will cause a induced voltage. | Applicable throughout the physical world. |

Basics of Magnetism

Magnetism is the force that is produced by the motion of electrons. That motion results in the attraction and repulsion of different objects. It is a ‘no-contact’ force, meaning that the magnet doesn't have to touch what it acts on. These magnetic forces and fields affect nearly every object to some extent.

Types of Magnetic Materials

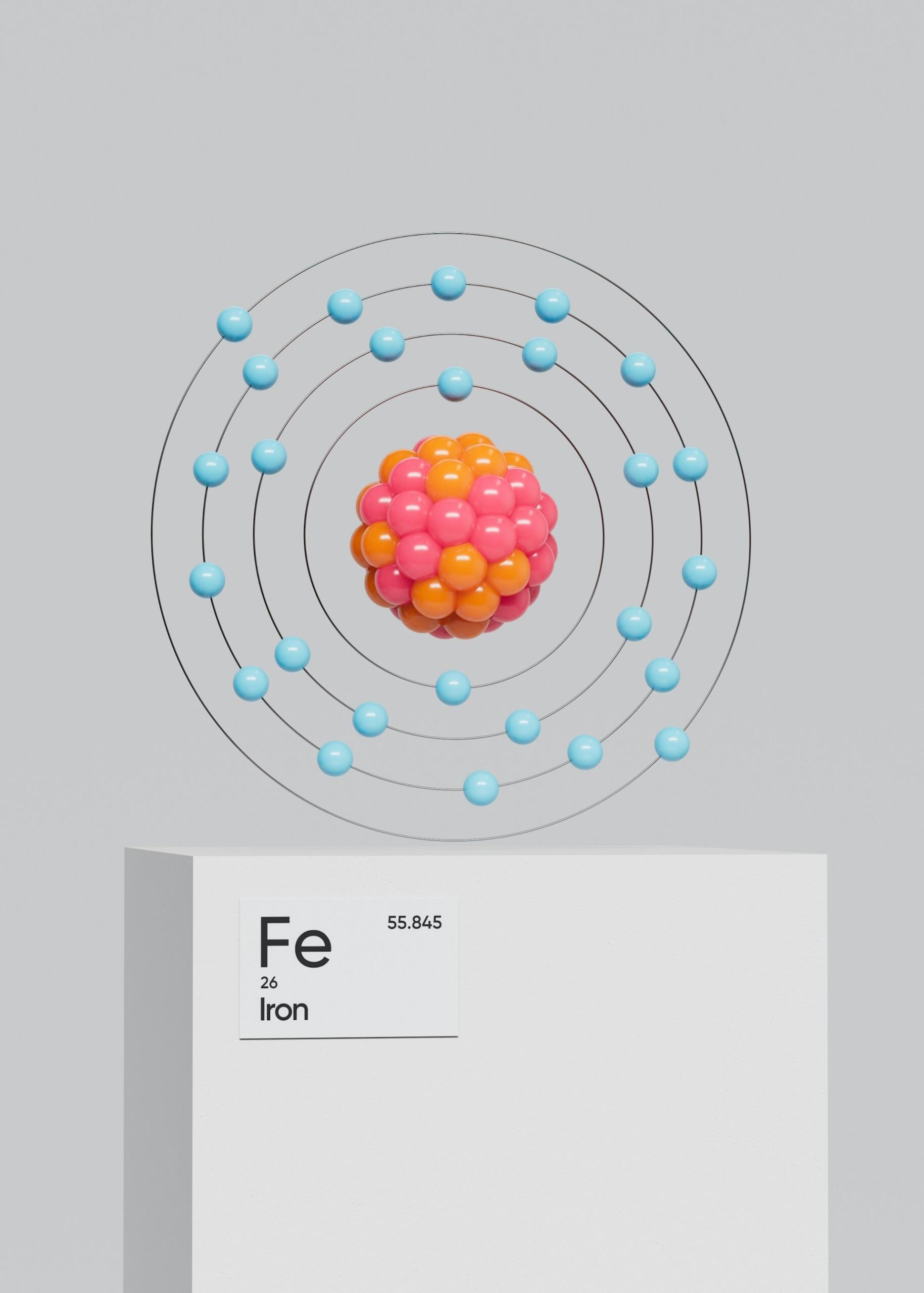

Every atom in a substance is made up of neutrons, electrons, and protons. Of them, the electrons are responsible for magnetism.

Typically, electrons ‘pair’ with those of an opposite charge, meaning that an electron with a negative charge should pair with one that is positive.

Thus, the material remains relatively stable, as each of the charges cancels the other out.

When substances have paired electrons, we refer to it as diamagnetism.

However, there exists many types of materials that have unpaired electrons. When this this condition exists, the substance becomes magnetic, as the unpaired electrons align.

In magnetic materials, electrons do not align, as the ‘magnetic moments’ of each of these individual electrons are not equal. That is, unless they are under the influence of an external magnetic field.

Paramagnetic substances only exhibit magnetism in the presence an external magnetic field.

Aluminum, magnesium and oxygen are examples of paramagnetic substances1. You might ask your physics teacher about the practical applications for these and other paramagnetic materials.

The ferromagnetic substances are the most useful substances for magnetic applications, by far. These are the magnetic materials with unpaired electrons of the same magnetic moment. They can become magnetic and will remain magnetic even after the removal of an external magnetic field.

Magnetic Forces and Fields

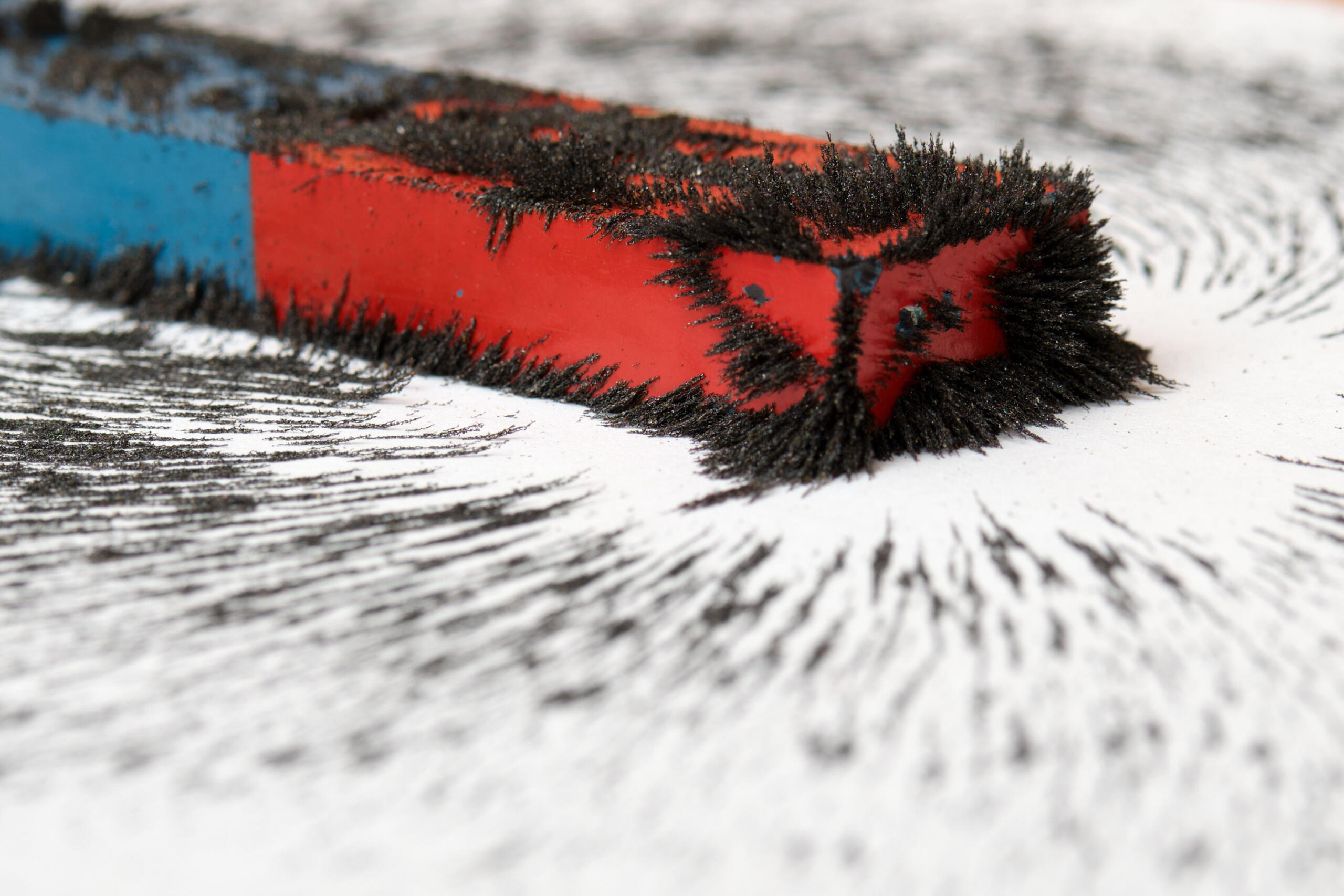

Every magnet or magnetic object has a magnetic field – the space around the magnet where its magnetic force is present.

Permanent magnets and electromagnets have enduring magnetic fields.

The strength of magnetic fields changes depending on the magnet. Powerful magnets have very strong magnetic fields while weaker ones exhibit smaller and less resilient fields. This strength (magnetic force) is measured in teslas (T).

A moving charged particle experiences magnetic force the moment it enters the magnetic field. This force is perpendicular to the velocity (speed) of the particle as it travels, as well as the magnetic field's direction. We can determine the force's direction using the right-hand rule.

1. Curl the fingers of your right hand into a loose fist.

2. Point your thumb upwards.

3. Your curled fingers indicate the magnetic field's direction.

4. Your thumb indicates the direction of the magnetic force.

What Is Electromagnetism?

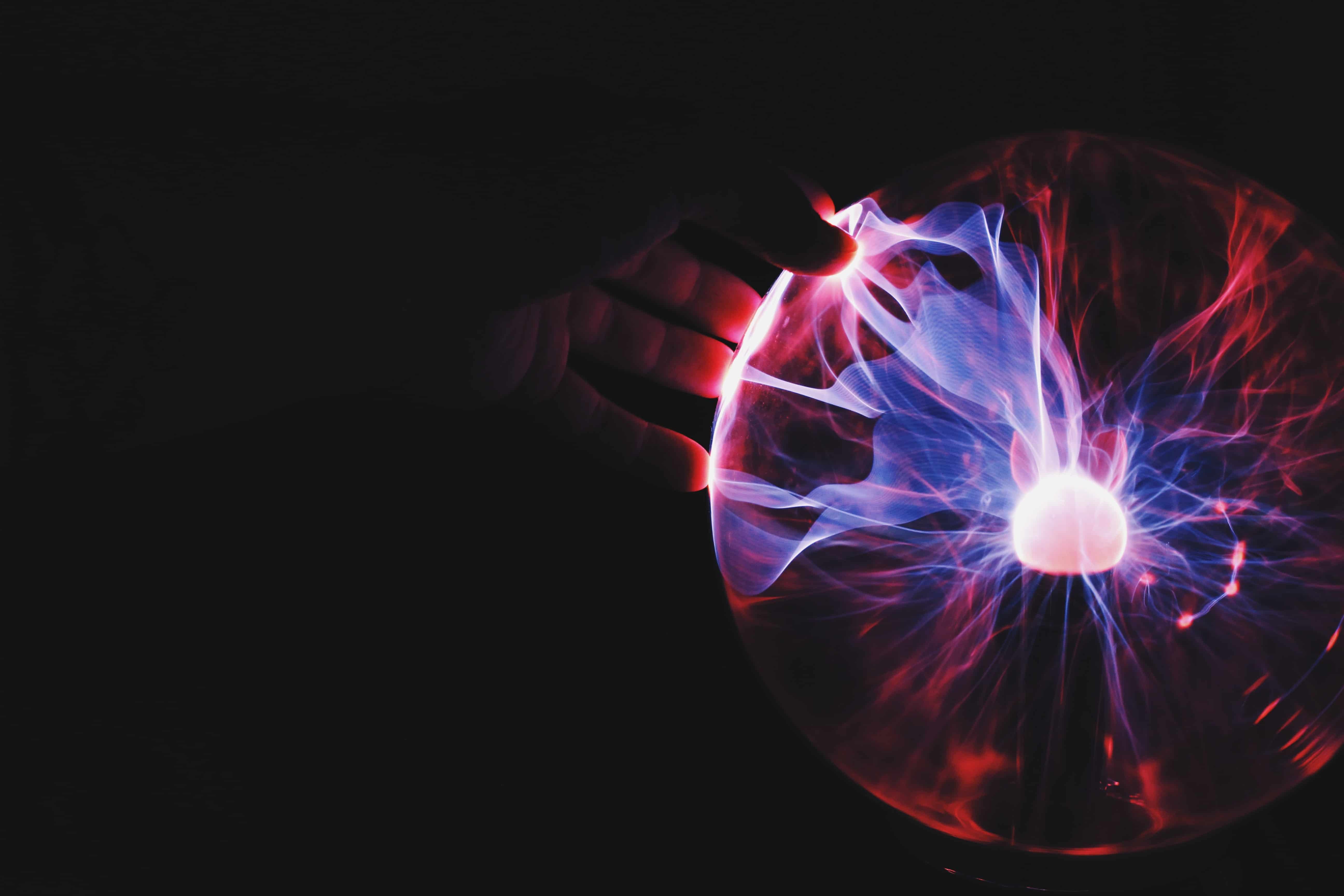

With magnetism explained, we can now ask: what happens when you add electricity to magnetic potential?

The link between magnetism and electricity is strong. We’ve just seen that electrons in a substance have a magnetic charge due to the fact of their movement within the magnetic material.

But the place in which electrons move the most is in electric current. After all, what is current but the movement of electrons?

As current moves through a wire, the wire becomes magnetized. The electrons' movement produces the magnetic field.

French physicist André-Marie Ampère discovered this phenomenon in 1820. He demonstrated his conclusions: parallel wires attract or repel each other, depending on which way the current flows. (He would later give his , by the way.)

André-Marie Ampère gave his name to the amp (ampere), the unit of electrical current.

The Relationship between Magnetism and Electricity

We know that electricity produces a magnetic field, and that magnetic fields rely on electrons. Therefore, major distinctions between magnetism and electricity is false. These are not discrete forces; they are closely intertwined. They are the same physical principle; two sides of the same coin.

The Englsh physicist, Michael Faraday, conducted many studies in electromagnetism. His work consolidated fundamental knowledge of electromagnetism in one concise law2. is one of the fundamental forces in the universe.

Any change in the magnetic environment of a coil of wire will cause a voltage (electromotive force or EMF) to be "induced" in the coil.

One obvious change you could make to a coil of wire is introducing current flow. Once you connect your coil to a power source, you induce electromotive force. In effect, you create an electromagnet. This clip shows the importance of Faraday's discovery.

How to Make an Electromagnet

Since the electromagnets of Faraday's time, the technology has not changed very much. Clever scientists have found ways to make them stronger but these magnets' overall structure has remained the same.

In fact, you can make such a magnet yourself, like the one in this picture.

As you can see, electromagnets consist of a coil of wire wrapped around a ferromagnetic core. The wire ends connect to a power source whose magnetic field is centred in the iron core.

We call these devices solenoids, and use them all the places where electromagnetism is active. As soon as the electric current is switched off, the solenoid ceases to be magnetic.

Applications of Electromagnetism

Practically from its discovery, this vital science found uses. The science of electromagnetic induction came about towards the end of the First Industrial Revolution. Inventors and industrialists fell onto this new technology in a frenzy.

Modern life would be impossible without magnetism and electromagnetism. Even something as pleasurable as listening to music, either through headphones or at a concert, would not be a thing.

Everything you see in this picture, from the robots to the lights, depends on this technology. Pretty much everything you own that's been manufactured came to be thanks to electromagnetism3.

You'll find the humble solenoid under your car's bonnet, switching on and off various engine components. They control your fridge's operation and numerous other applications, besides. Its design hasn't changed much over the centuries since Faraday built the first model.

On the industrial scale and in laboratories, we find the most powerful electromagnets. For instance, the cranes that offload shipping containers in our ports contain electromagnets capable of lifting several tons. By contrast, CERN's Large Hadron Collider runs on specialised electromagnets4.

Every appliance in your home needs electromagnetism to function. One of the latest cookware innovations, the induction hob, is nothing more than an electromagnet.

Even the electricity that comes into our home relies on electromagnetic properties. High-voltage electricity is generated far from population centres, flowing along power lines till it reaches our neighbourhoods. There, step-down transformers use electromagnetism to reduce the load to a safe voltage.

Applications of Magnetism

If electromagnets do all that, is there any work left for magnets to do? For a quick answer, take a look at your refrigerator door. That squishy rubber part that runs around it houses a magnet to keep the door closed. And that's just the start of our list5.

Dig into your wallet and take a look at your bank card (or any other card with a dark strip on the back).

That magnetic strip stores information about you that links you to your bank account (or other utility). No electricity in these magnets, just information.

Which takes us to electronic devices.

Throughout your television, tablet, laptop, and phone, tiny magnets ensure your devices' proper operation and store information. Delicate medical devices like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines full of magnets.

We could go on but you likely get the point. Our world is magnetic and we don't have to think too hard to find instances of our everyday magnet usage.

Magnetism For Students: Experiments You Can Try at Home

If you take a physics course online, you'll likely have to complete a few experiments to earn your grade. Why wait till then to discover magnetism for yourself?

Note: hold your magnet to an unburnt match head to see its reaction.

Finally, if you happen to have an old cassette or video tape lying around, you can erase everything on it by waving or placing a magnet on it. Like your bank card magnetic strip, these tapes' information is magnetically contained. Once you introduce another magnet, that info disappears!

Resources and Further Reading on Magnetism and Electromagnetism

- Dr Anne Marie Helmenstine: https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-paramagnetism-605894

- R. Nave: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/farlaw.html

- Dhara: https://uniboardhub.com/blog-detail.php?post=what-is-an-electromagnet-uses-in-daily-life-and-industries

- CERN: https://home.cern/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider

- Cathy Marchio: https://www.stanfordmagnets.com/list-of-magnet-applications-in-practical-life.html

Summarise with AI: